A Good ML Theory is Like Physics -- A Physicist's Analysis of Grokking

Only calulate after you know the answer.

Machine Learning (ML) has demonstrated impressive empirical performance on a wide range of applications, from vision, language and even science. Sadly, as much as theorists refuse to admit, recent developments in ML are mainly attributed to experimentalists and engineers.

This calls for the questions:

- (Q1) Do we really need theories of ML?

- (Q2) If so, what do good ML theories look like?

Trained as a physicist, I am always fascinated by the way physicists approach the reality. Usually a mental picture is formed, and a lot of useful predictions can be made even without the need to write down any math equations. Physicists are good at identifying important factors in problems, while neglecting irrelevant factors — To me, the “Spherical chicken in the vacuum” joke sounds more like a compliment rather than teasing. As a physicist, it is always satisfying to have a theory for certain phenomenon, but the theory is not necessarily a pile of enigmatic mathematical symbols or equations. What physicists really care about is how well our theory can describe reality (the goal), not how (tools used to reach the goal). My personal and perhaps biased feeling for (most) current ML theories is that: these theories focus too much on the tools to notice they are actually deviating from the original goal.

Consequently, my personal take to the questions posed above are:

- (A1) Yes, we do need ML theories.

- (A2) Good ML theories should be “physics-like”. In short, they should place emphasis on reality, admit intuitive mental pictures, have predictive power, and finally guide future experiments.

It is worth mentioning that “physics-like” ML theory does not only mean certain tools in physics, or certain physical phenomenon, but also (more importantly!) the mindset that physicists adopt to approach our physical reality (will be made precise). This blog consists of three parts:

- (a) Why do we need theory? I will review the philosophy of theory in science.

- (b) Physics-like ML theory. I will define “physics-like” ML theory.

- (c) An example: Grokking. I will demonstrate the power of “physics-like” thinking applied to demystify “grokking”, one puzzling phenomenon.

Why do we need theory?

You may think the word “theory” is a niche term for science nerds, but we all human beings have a theory carved in our DNA: To survive and win the natural selection game, we must have understood the theory of the physical world around us, without even realizing it. If you go look up the word “theory” in a dictionary, you will get something like this:

“A supposition or a system of ideas intended to explain something, especially one based on general principles independent of the thing to be explained.”

Two takeaways from this definition: (1) a theory is intended to explain something X. (2) a theory is based on principles independent of X. These two point can be elegantly unified from an information-theoretic perspective. (1) is saying that the theory simplifies X (information compression). (2) is saying that the theory can predict X (information gain).

Let me elaborate more. Assume we were in our ancestors’ position and don’t know about the cycle of four seasons, we want to know when to reap and sow. Can we just document temperature and other conditions everyday, without trying to figure out a theory (i.e., every year has four seasons) for it? This is no good at all! It is too redundant, failing the information compression criterion. Also, it cannot provide anything useful about the future, failing the information gain criterion. So, it is clear that a good theory should be able to do information compression to past observations, and can obtain information gain (i.e., have predictive power) for future experiments/observations.

I like this “Strong Inference” paper published in Science in 1964, discussing about what good theories look like. I especially like the quote “A theory which cannot be mortally endangered cannot be alive”. If a theory predicts a thing that nobody believes (”mortally endangered”), but finally it turns out that thing actually happens, this is a strong signal that the theory is undeniably true (“alive”). This is again aligned with the information gain criterion: a lot of surprisal (information) is gained from the theory. The author also quote the “Eightfold Way” example, where particles physicists managed to unify eight mesons under a simple Lie group SU(3) (information compression) and predict the last missing particle (information gain).

“Physics-like” ML theory

Physics has been playing a huge role in understanding and improving machine learning. Physics can help ML technically, by offering tools and concepts that physicists have developed for hundreds of years. There have been great examples where physicists use their toolkits to tackle problems in ML. One well-known example is to apply field theory analysis to deep neural networks (DNNs). Since DNNs are special kinds of complex systems and dynamical systems that physicists have always been dealing with, maybe it is not that surprising that physicists have off-the-shelf toolkits immediately useful for DNNs.

Although physics can help ML technically, I want to argue that, more importantly, physics can help ML philosophically. This is something I found quite fundamental and potentially game-changing, but I don’t yet know many people sharing the same intuition. That’s why I’m writing this blog.

So when I say “physics-like”, I don’t necessarily mean technical tools or concepts in physics, but rather a mindset that physicists adopt to approach our physical reality. The physicists’ mindset is:

- (1) Reality. We put an emphasis on reality.

- (2) Simplicity. We view simplicity as beauty.

- (3) Dynamics. We view the world dynamically rather than statically.

- (4) Intuition. We appreciate mental pictures more than (vacuous) math rigour.

- (5) Control. We design well-controlled experiments to test our theory.

Of course the list goes on and on, but to me personally, these strategies really help me in my quest to understanding ML. I’ll now use a concrete example to illustrate how these physics-like thinking help me understand ML.

An example of physics-like thinking: Grokking

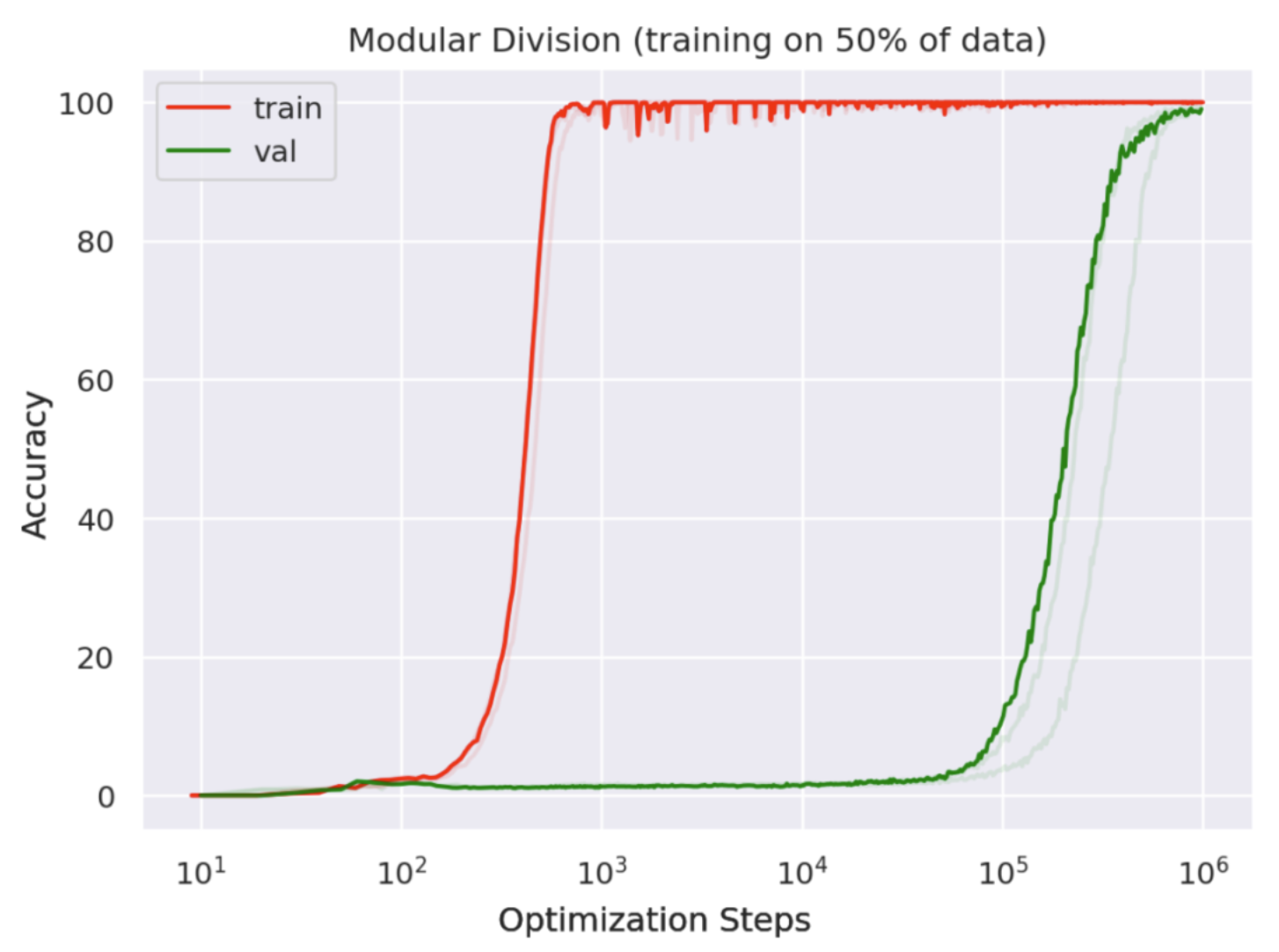

About two years ago, when we were doing a journal club, an OpenAI paper called “grokking” immediately caught my eyes. The paper found that, for neural networks trained on algorithmic datasets, generalization happens long after memorization (see the accuracy curves below, from their paper).

This is quite striking to me, since we normally don’t see such huge delays on standard ML datasets, e.g., image classifications. This sounds like: a neural network is a student who is diligent but not so smart, who first tries to memorize everything in the textbook without understanding them, but eventually has a Eureka moment when understanding happens (“grokking”). I was thinking, this weird phenomenon must have a dynamical reason behind it. I was enchanted by this phenomenon – To me, it is as exciting as a new particle being discovered in physics, here a “grokkon”. I decided to understand grokking in my own way, and I strongly feel that a “physics-like” theory is probably most promising.

Simplicity: Identifying relevant variables

When a physicist say “I have a solution but it only works for spherical chickens in a vacuum!”, I appreciate it a lot since it is really saying “What matters most is the size of the chicken”. This is a reasonable and smart simplification, as long as it can answer the target question. It is widely agreed in physics that “Everything should be made as simple as possible, not but simpler”.

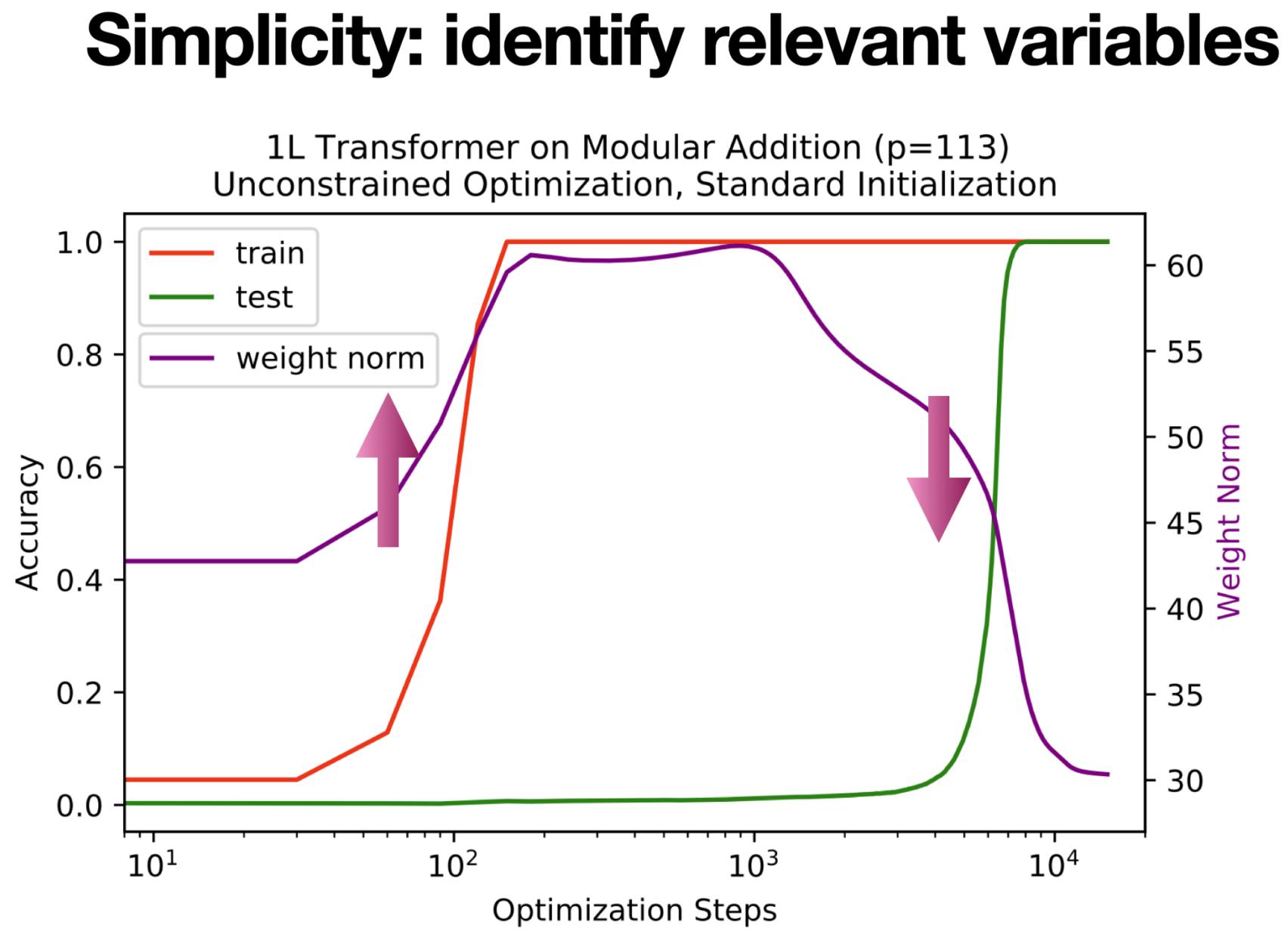

Coming back to the grokking case, I was wondering: what is the most important factor here? Now recalling the diligent student analogy: At first, the neural network memorizes the whole training datasets by rote learning; then the neural network finds a simpler solution which requires memorizing much fewer samples. So the relevant variable here is the number of memorized samples. Although the number of memorized samples is not observable (at least I don’t know how to estimate it), intuitively it is related to the complexity or capacity of the neural network. Now the question becomes: which complexity measure is relevant here? The number of parameters is of course not appropriate, because the architecture (hence the number of parameters) is fixed in training. This is when the weight norm w (\(L_2\) norm of weight parameters) came to my mind. To verify that the weight norm is relevant to grokking, we keep track of the weight norm (purple curve below). We found that weight norm is highly correlated with overfitting and generalization. When overfitting happens (~50-100 step), the weight norm increases; when generalization happens (~5000-10000 step), the weight norm decreases. This observation is aligned with the diligent student analogy: the student tries to memorize everything (need more capacity, i.e., large weight norm), and then manages to simplify things (need fewer capacity, i.e., small weight norm).

Dynamics: Viewing the world dynamically**

After identifying that the memorization circuit has a large weight norm, while the generalization circuit has a small weight norm, our next question is: how does the neural network transit from the large norm state to the small norm state? What is the dynamics? This is a natural question physicists would ask – everything must have a dynamical origin. What is observed now must be originated from something in the past. Our physical universe has a time dimension, so are neural networks (time = training step).

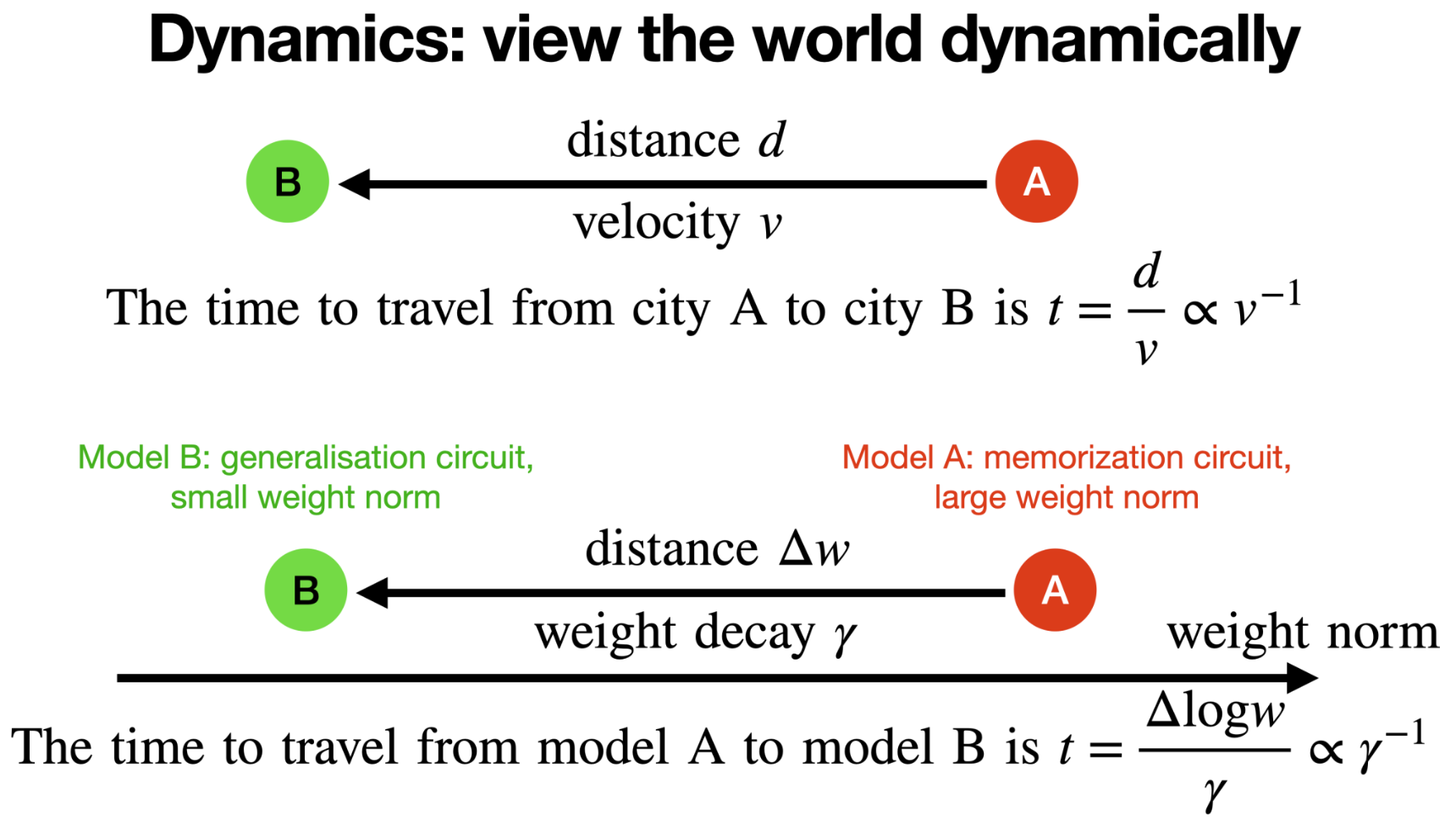

After overfitting, the training loss is almost zero, hence the gradients of the prediction loss is almost zero. The only explicit force that drives the model to change is weight decay. The role of weight decay \(\gamma\) is to reduce the weight norm. If we view the weight space as our physical space, then the weight decay plays the role of velocity along weight norm. From elementary school, we know that a traveller needs to spend time \(t=d/v\propto v^{-1}\) to travel along distance d from city A to city B with velocity \(v\) (see Figure below). Analogously, it takes \(t\propto \gamma^{-1}\) to “travel” from circuit A (memorization, large norm) to circuit B (generalization, small norm).

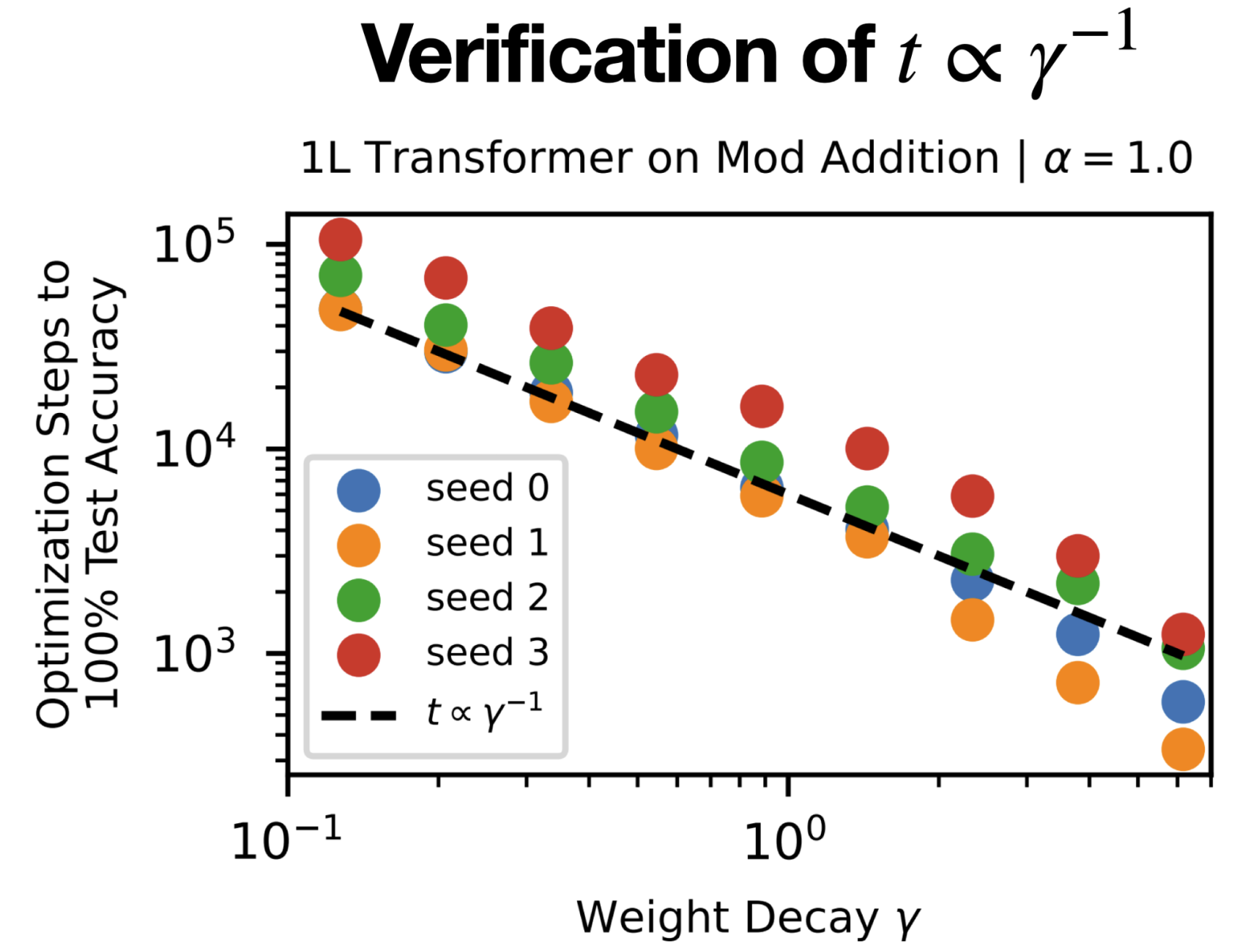

It is worth noting that the time to generalize \(t\propto\gamma^{-1}\) is a prediction our theory makes. It is “mortally endangered” in the sense that this simple relation sounds too good to be true. However, this is indeed true! We were able to verify the inverse relation in experiments (see below).

Intuition: Forming mental pictures

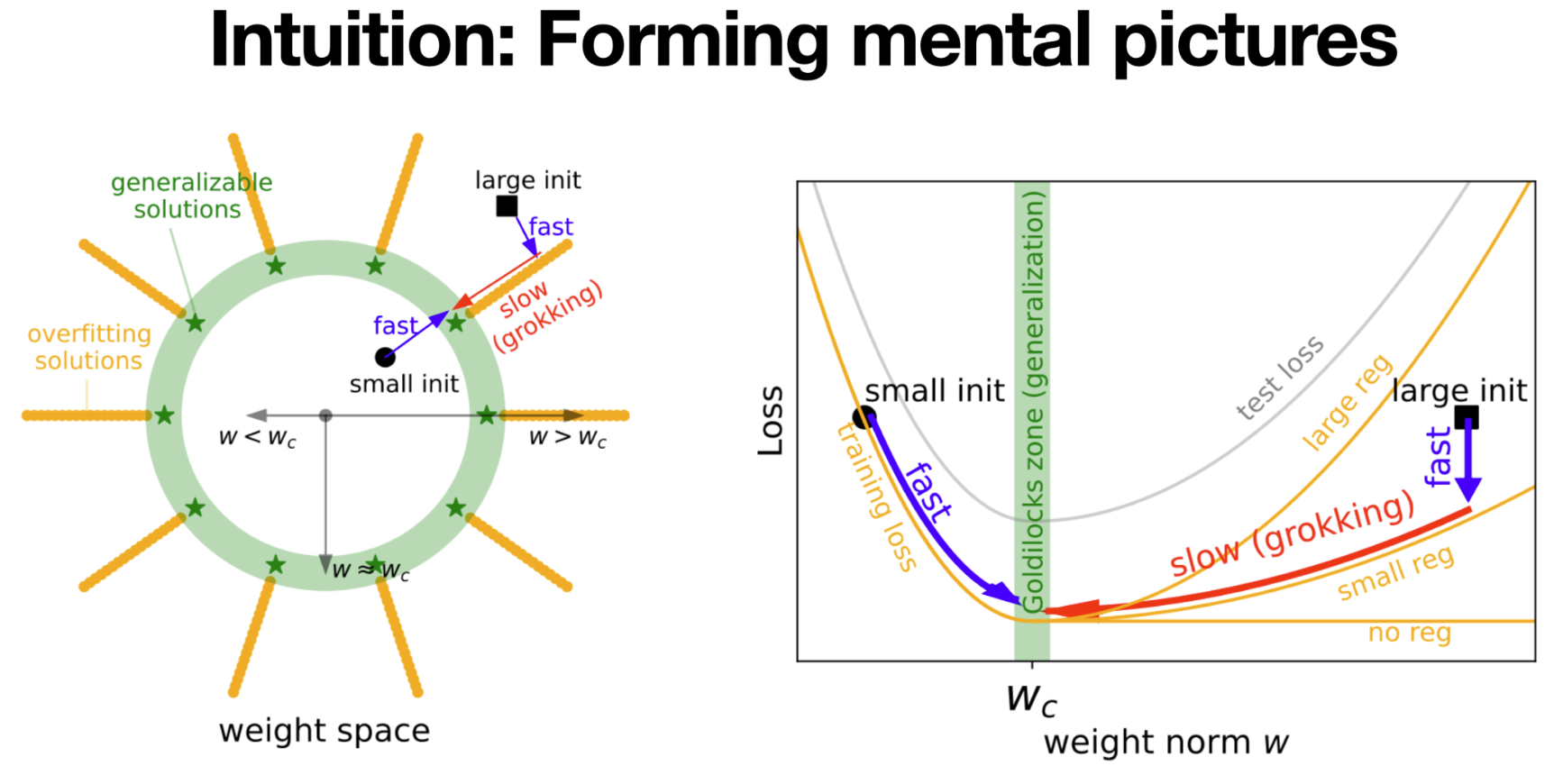

Although the above theory makes quite accurate predictions, it is a bit oversimplified, and does not provide a global picture for loss landscapes. I hope to have a more detailed mental picture (but still, as simple as possible).

The mental picture is (figure above, left): in the weight space of model parameters, there exists a hypersphere w=w_c where all generalization solutions lie on (called “Goldilocks zone”, in green). Inside the sphere are underfitting solutions (non-zero training loss). Outside the sphere, there are many overfitting solutions, connected as valleys (in orange). When the neural network is initialized to have a large norm (black square), it will first quickly goes to a nearby overfitting solution, but then slowly drifts along the overfitting valley towards the hypersphere. The velocity of the drift, as we discussed above, is proportional to the weight decay, which is usually set to be small in NN training.

We can further simplify the picture (figure above, right) to 1D: since we only care about weight norm, we plot train/test losses against it. The training and test losses would look like “L” and “U”, respectively. Grokking happens when the neural network lands on the large weight norm region (where the shape of “L” and “U” mismatch).

Control: Eliminate grokking

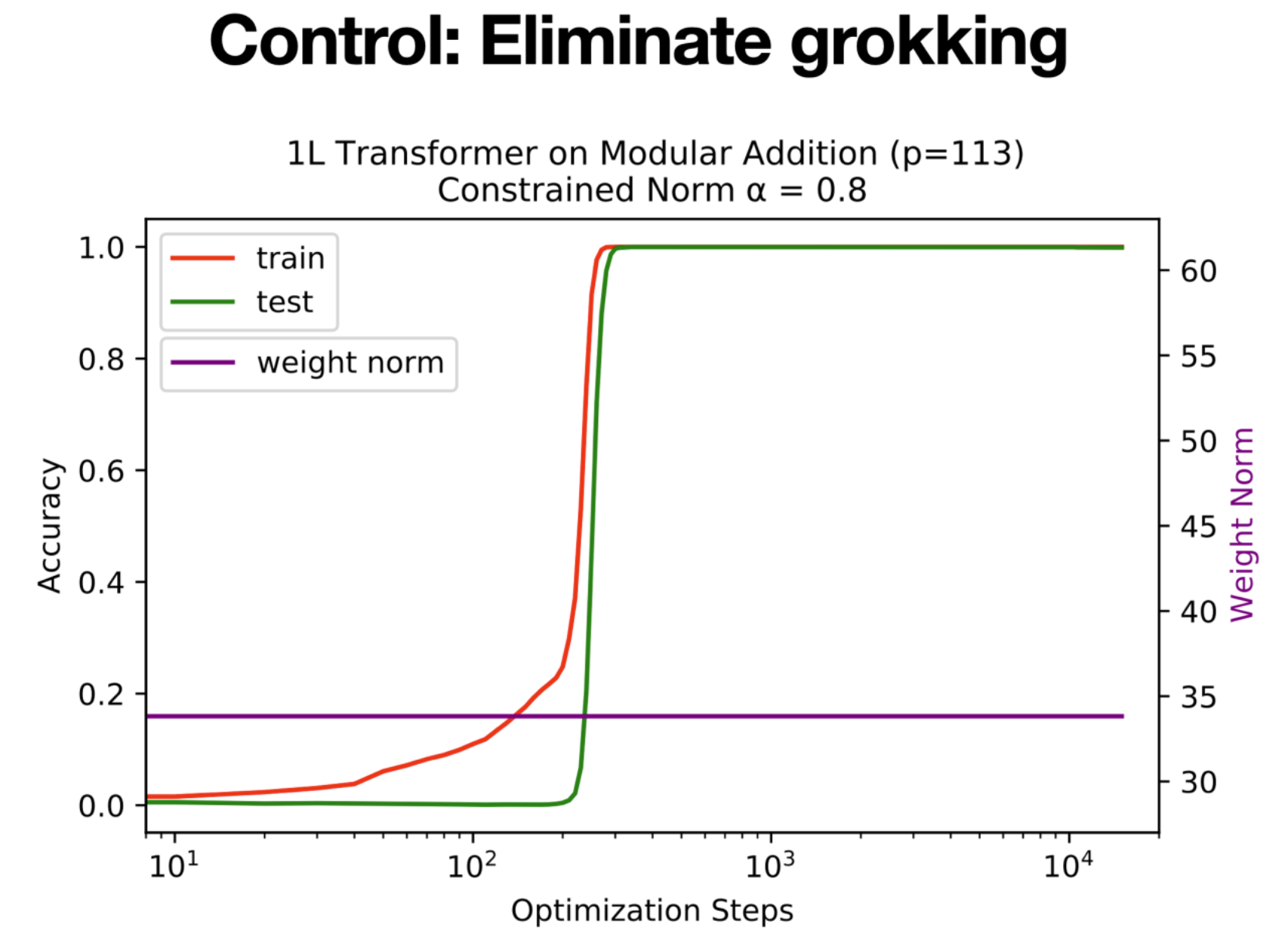

Since grokking is undesirable, our final goal is to control(i.e., eliminate) it. The mental picture suggests that grokking happens due to too large weight norms. This, on the other hand, suggests that constraining the model to have a small weight norm can help eliminate grokking. We set the initialization to be small, i.e., 0.8 times the standard initialization, and constrain the weight norm to be constant in training. We found this strategy indeed eliminates grokking!

We end up publishing two papers on grokking at NeurIPS 2022 (Oral) and ICLR 2023 (Spotlight), although at first I was very concerned that ML community would not appreciate such “physics-like” papers. This makes me happily realize that ML community, just like the physics community, do appreciate mental pictures and care about reality, although researchers in the ML community have long been unwillingly involved in the arms race of (most times) vacuous mathematical rigour.

Closing Remarks

In this blogpost, I described a mindset that physicists adopt in physics research, and argue that this mindset is also beneficial to ML theory research. To have such physics-like way of thinking, one doesn’t need to be a physicist oneself, but really the point is to focus on the goal (understanding ML) rather than the tool (vacuous math rigour). I do believe that best ML practitioners are physicists at heart: they may have the mental pictures deep in mind without even realizing them! My research goal is to make these mental pictures explicit and accessible to anyone who is willing to understand: a good physicist can even let his/her grandma appreciate the beauty of physics!

Enjoy Reading This Article?

Here are some more articles you might like to read next: