Sparse attention 6 -- In-context Associative recall

Author: Ziming Liu (刘子鸣)

Problem setup

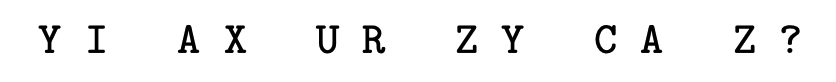

This article aims to reproduce the in-context associative recall task from the paper “The emergence of sparse attention: impact of data distribution and benefits of repetition”. The task is as follows: given a sequence,

the model must output Y, since the query Z matches the key in the Z–Y pair appearing earlier in the context.

I am particularly interested in Figure 4 (left) of the paper (shown below), which demonstrates that learning is significantly delayed when the context length is large (with the context length being twice the number of pairs). In that regime, it takes about \(10^5\) steps for in-context learning (ICL) to emerge. My intuition is that learning can be substantially accelerated by choosing appropriate hyperparameters. For example, I would expect that a smaller embedding dimension could lead to much faster learning, whereas the paper uses an embedding dimension of 256.

Dependence on embedding dimension

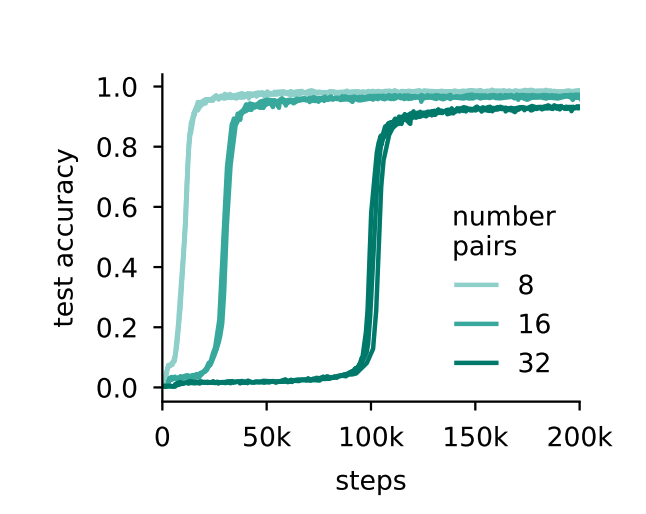

We use a 2-layer, attention-only transformer model with embedding dimension \(N\) (swept), training data size \(10^4\), vocabulary size 64, and 32 key–value pairs. The model is trained using the Adam optimizer with learning rate \(10^{-2}\). While the original paper uses an embedding dimension of 256, we hypothesize that much smaller embedding dimensions can already succeed.

Indeed, we find a Goldilocks zone in which ICL emerges in fewer than 1000 steps. Both too small and too large embedding dimensions lead to failure. An embedding dimension of 60 is particularly interesting: the model initially learns but then becomes unstable, likely due to an excessively large learning rate.

How to make large embedding dimensions work

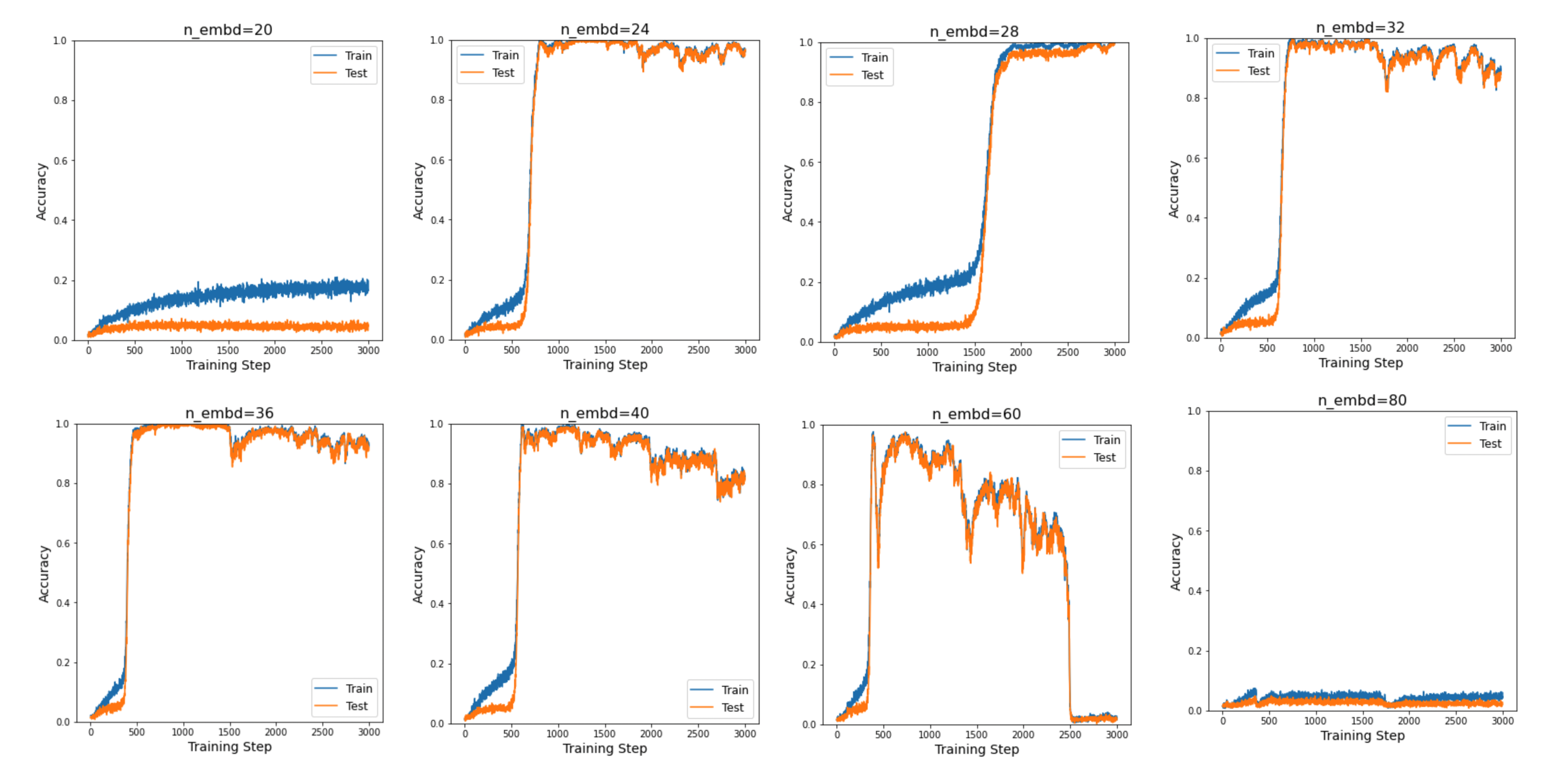

When one is forced to use a large embedding dimension for some reason,

- the data size should be increased to mitigate overfitting;

- the learning rate should be reduced, in line with the common wisdom that wider networks require smaller learning rates. This is why learning is slow for large embedding dimensions.

We sweep over data sizes \(\{10^4, 10^5\}\) and learning rates \(\{10^{-2}, 10^{-3}\}\):

More systematically, it would be interesting to draw phase diagrams capturing how learning curves depend on various hyper-parameters.

Comment: Link to learning rate warmup

For patterns with very strong signals that can be learned very early (induction is arguably a strong pattern due to its commonality), keeping a large learning rate will eventually make them unstable. Therefore, in the early stage, a relatively small learning rate is needed to prevent these strong-signal components from becoming unstable. In the later stage, however, we want to accelerate the learning of weaker signals, which calls for a larger learning rate. This is simply a hypothesis which requires further justification.

Induction heads are likely such strong-signal components. This also connects nicely to the earlier discussions on learning-rate schedules.

Code

Google Colab notebook available here.

Citation

If you find this article useful, please cite it as:

BibTeX:

@article{liu2026sparse-attention-6,

title={Sparse attention 6 -- In-context Associative recall},

author={Liu, Ziming},

year={2026},

month={January},

url={https://KindXiaoming.github.io/blog/2026/sparse-attention-6/}

}

Enjoy Reading This Article?

Here are some more articles you might like to read next: