Sparse attention 5 -- Attention sink

Author: Ziming Liu (刘子鸣)

Motivation

This article studies how an attention sink can emerge in a single-layer (1L), attention-only transformer.

Problem setup

Dataset

When all previous tokens are useless for predicting the next token, the ideal attention weights would be zero everywhere. However, due to softmax normalization, attention must be allocated somewhere. As a result, if a [BOS] token is present at the beginning of the sequence, it can serve as a reservoir that absorbs attention.

We use the unigram toy dataset (defined in unigram toy), where the next token does not depend on any previous tokens, but is instead drawn independently from a token-frequency distribution.

Model

A 1L attention-only transformer. For simplicity, we remove positional embeddings.

Experiment 1: Unigram dataset

Including [BOS]

We choose the embedding dimension to be 2 and the vocabulary size to be 101 ([BOS] + 100 tokens whose frequencies follow Zipf’s law). This configuration already performs the task perfectly (in fact, \(n_{\rm embd}=1\) suffices, as discussed in unigram toy).

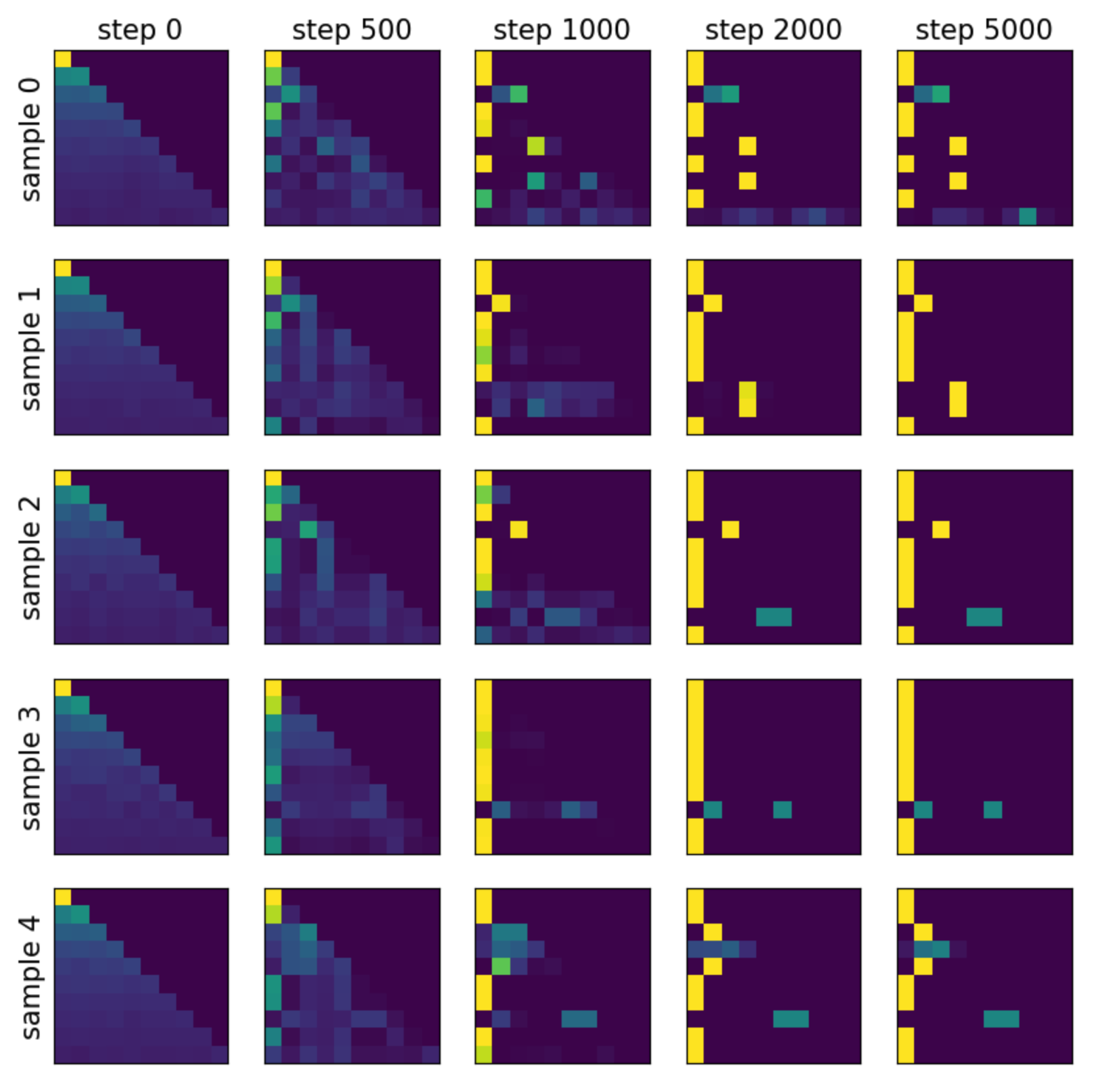

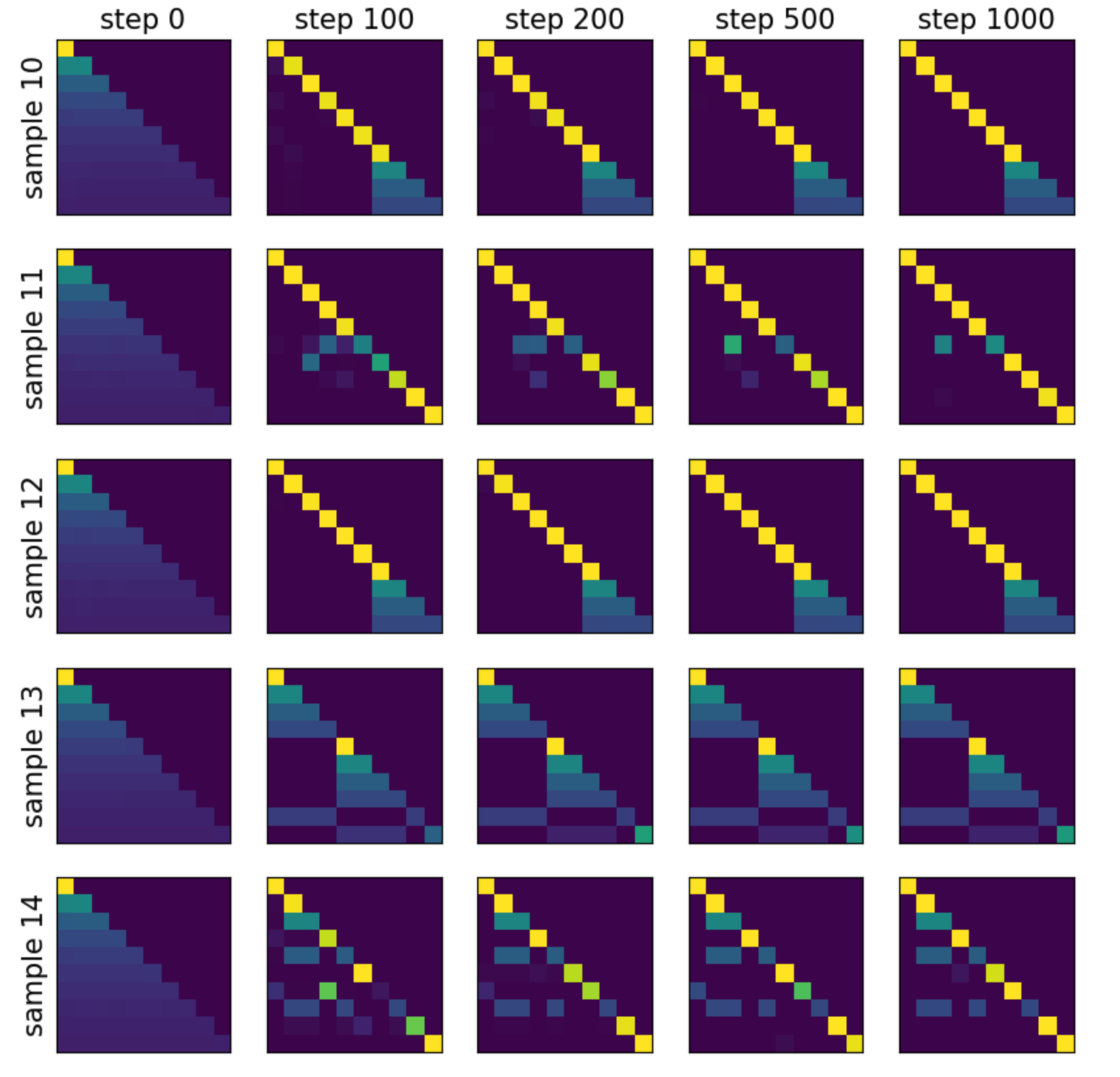

The attention maps are shown below. Each row corresponds to a different sample, and each column corresponds to a different training step. Besides the [BOS] token, frequent tokens are also used to absorb attention.

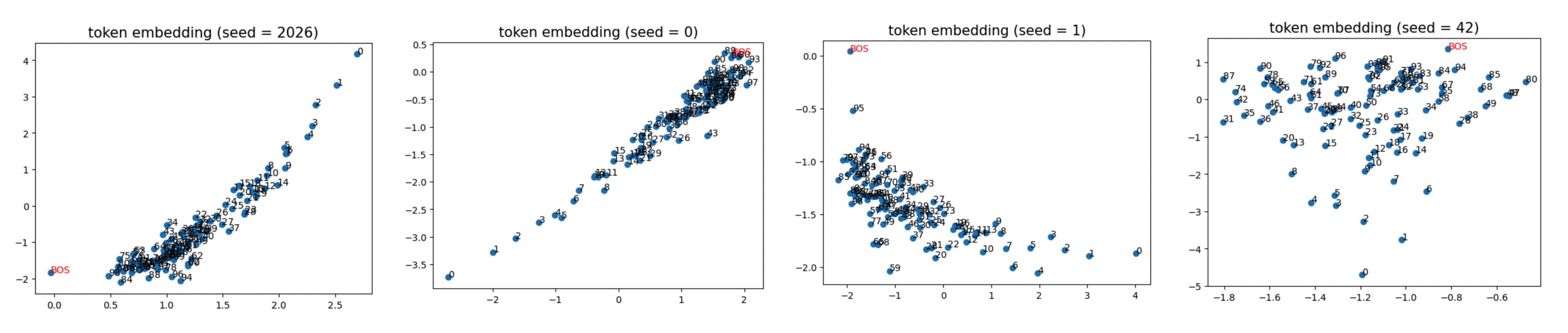

The token embeddings for four different random seeds are shown below:

Recall that we set token frequencies to follow a Zipfian distribution, so small-index tokens (e.g., [0]) appear more often than large-index tokens (e.g., [99]). Interestingly, large-index tokens are closer to [BOS] than small-index tokens in embedding space. Since [BOS] is heavily attended to, this implies that large-index (infrequent) tokens receive more attention than small-index (frequent) tokens. This likely occurs because attention to frequent tokens is more strongly suppressed than attention to infrequent tokens.

Indeed, it has been observed in large language models that their embedding spaces contain a direction correlated with token frequency. Our toy model offers one plausible explanation: this structure emerges for the same reason as the attention sink.

Excluding [BOS]

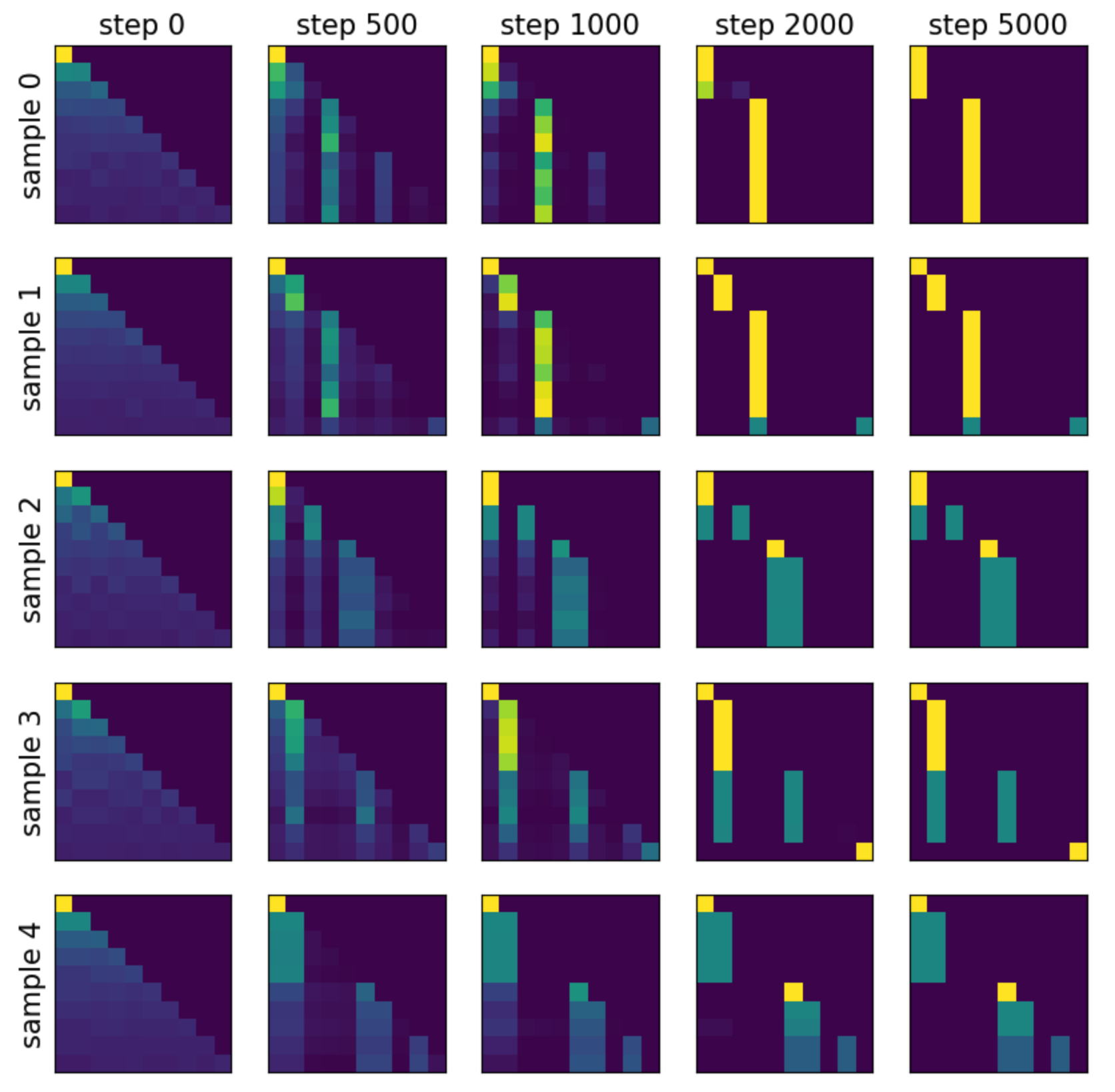

When [BOS] is not present, attention sinks still emerge, and these sinks correspond to frequent tokens (with low indices, e.g., [0], [1]).

The five sequences are:

\[[ 1, 4, 88, 0, 6, 93, 1, 63, 9, 32]\] \[[ 3, 2, 57, 0, 5, 9, 3, 20, 67, 0]\] \[[ 1, 15, 1, 84, 0, 0, 5, 18, 53, 18]\] \[[ 5, 1, 7, 10, 6, 1, 5, 73, 2, 0]\] \[[ 1, 1, 17, 25, 46, 0, 0, 88, 0, 5]\]Experiment 2: Bigram dataset

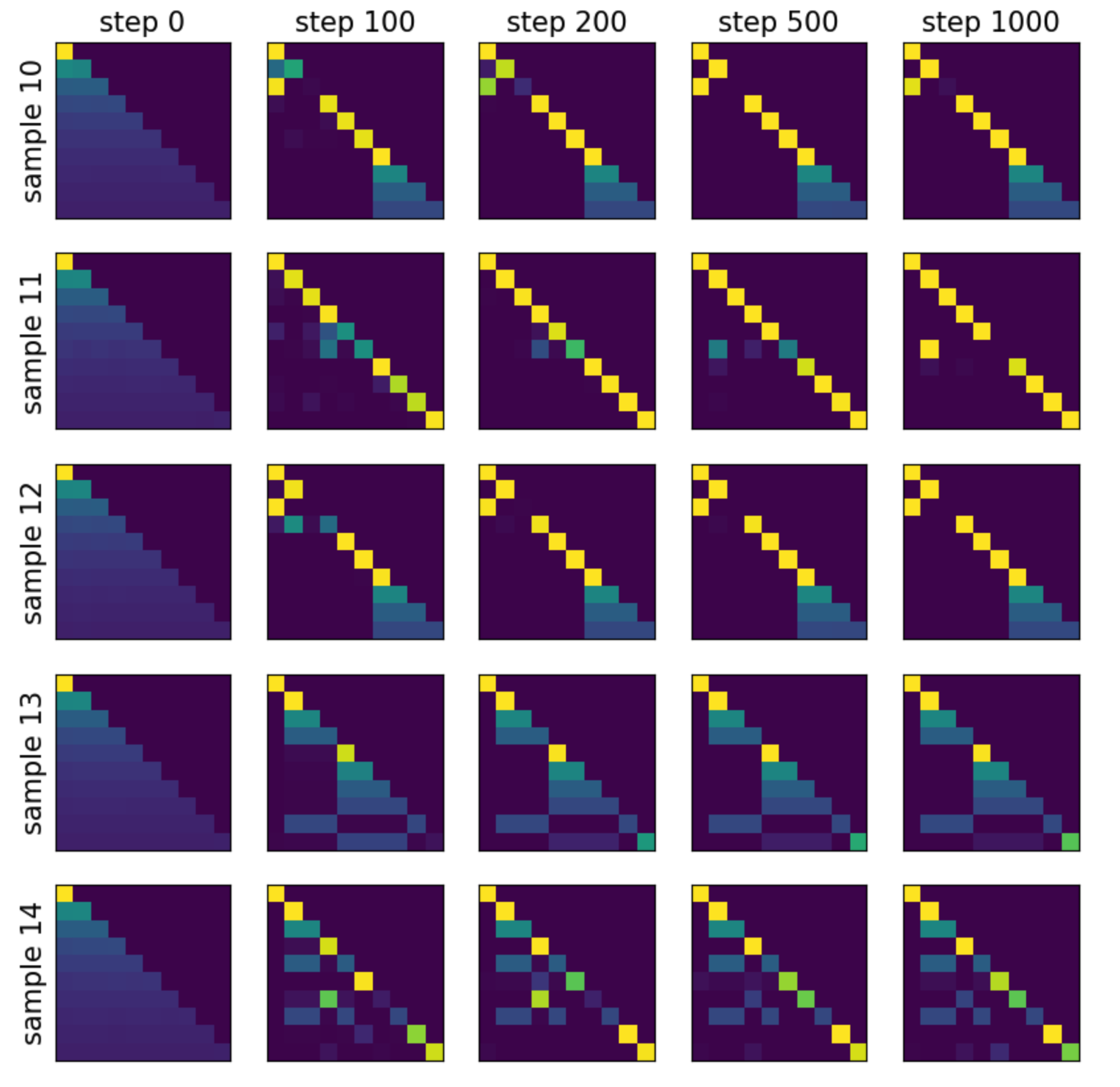

We now switch to a bigram toy dataset defined in bigram-3. In this setting, the next token depends on the current token, so the ideal attention pattern would be a diagonal matrix.

Including [BOS]

The attention pattern is nearly diagonal, except for splitting among identical previous tokens. In addition, some tokens incorrectly attend to the [BOS] token (e.g., the 3rd token in example 10 and the 3rd token in example 12).

Excluding [BOS]

The attention pattern is again almost diagonal, with the main deviation being splitting among identical previous tokens.

Code

Google Colab notebook available here.

Citation

If you find this article useful, please cite it as:

BibTeX:

@article{liu2026sparse-attention-5,

title={Sparse attention 5 -- Attention sink},

author={Liu, Ziming},

year={2026},

month={January},

url={https://KindXiaoming.github.io/blog/2026/sparse-attention-5/}

}

Enjoy Reading This Article?

Here are some more articles you might like to read next: