Sparse attention 2 -- Unattention head, branching dynamics

Author: Ziming Liu (刘子鸣)

Motivation

In the previous blog, we found that a single-layer attention model (without positional embeddings) can learn to copy the current token. But what about copying earlier tokens? Since positional embeddings are missing, it seems impossible to determine where each token is located in the sequence. Under this reasoning, the task should be unsolvable, and I would expect the loss to be \({\rm log}(V)\), or equivalently the perplexity to be \(V\), where \(V\) is the vocabulary size.

As we show below, however, the story is more subtle.

Problem setup

Dataset

The task is to copy the previous token. Taking context length = 4 as an example, this corresponds to

\([A][B][C][D] \rightarrow [C]\).

In fact, due to the absence of positional embeddings, and because attention is equivariant under permutations of previous tokens, copying any previous token defines an equivalently difficult task.

Model

We stick to the toy model from the previous blog. The model consists only of an Embedding layer, an Unembedding layer, and a single Attention layer, with no MLP layers.

Observation: loss plateau, embedding branching dynamics

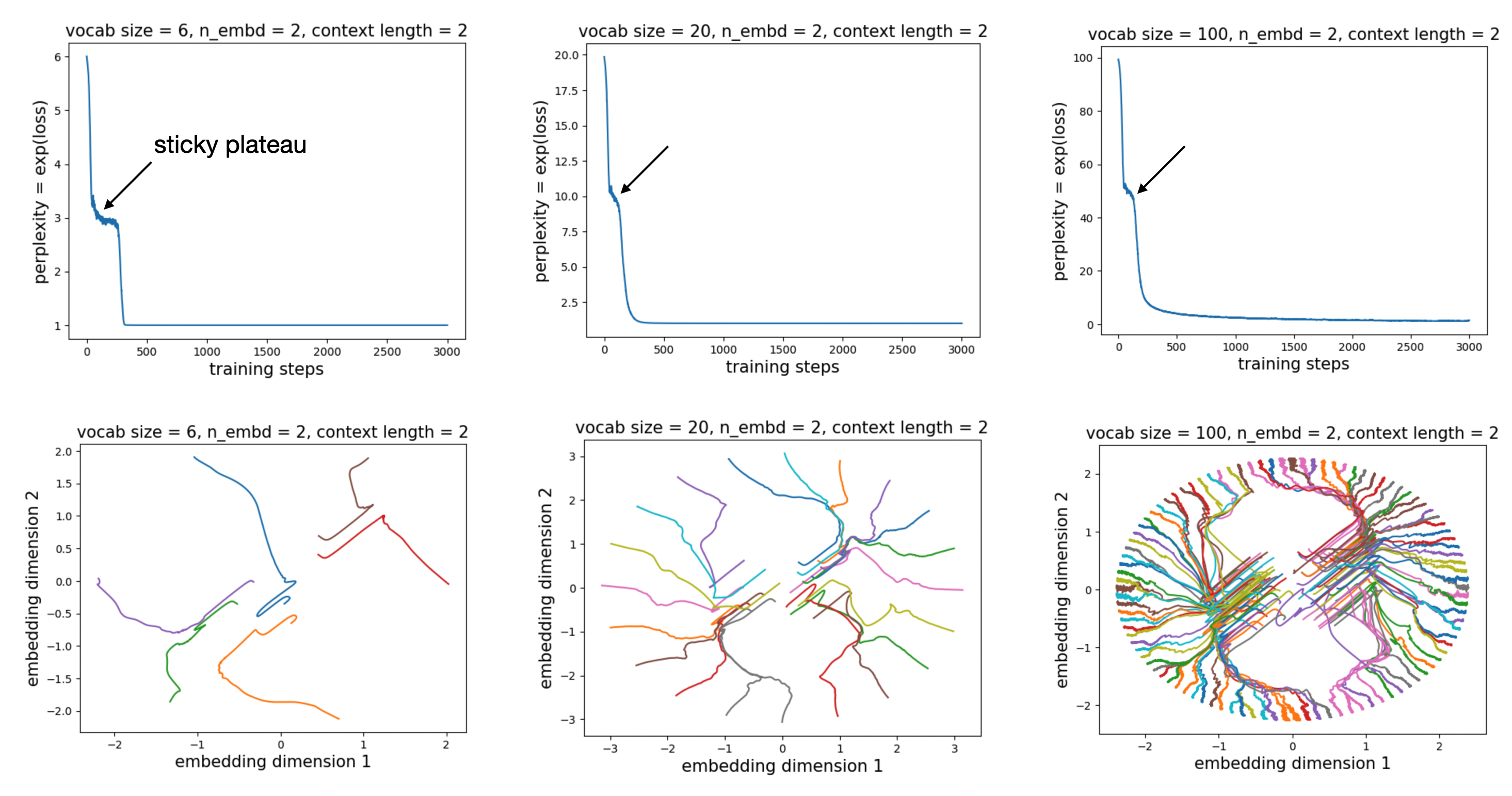

We examine the loss curves (in practice, we plot perplexity, i.e. \({\rm exp(loss)}\)). For embedding dimension = 2 and context length = 2 (task: \([A][B]\to[A]\)), as we vary the vocabulary size, we consistently observe a sticky plateau (as in the previous blog), where the perplexity is approximately half of the vocabulary size.

By visualizing the evolution of the embeddings, we find that the dynamics proceed in two stages. In the first stage, there is a dominant direction along which the embeddings expand. Only in the second stage do the embeddings begin to move along the orthogonal direction, eventually forming a circular structure. This second stage also exhibits interesting branching dynamics:

What’s happening?

My first reaction was: how could this task possibly be solved? The low final loss clearly indicates that the model must have developed some internal algorithm to accomplish it. The emergence of circular embeddings is particularly suggestive, hinting that the model has learned something nontrivial and elegant.

We can inspect the learned \(W_Q/W_K\) matrices (\(W_V\) is unimportant here since we only care about the attention pattern):

\[W_Q = \begin{pmatrix} 13.24 & -3.40 \\ -3.28 & -14.7 \\ \end{pmatrix}, \quad W_K = \begin{pmatrix} -14.03 & 3.56 \\ 3.19 & 13.99 \\ \end{pmatrix}\]We observe two numerical clusters (ignoring signs): one around 13 (denoted \(a\)), and another around 3 (denoted \(b\)). We therefore approximate them by the following symbolic forms:

\[W_Q = \begin{pmatrix} a & -b \\ -b & -a \\ \end{pmatrix}, \quad W_K = \begin{pmatrix} -a & b \\ b & a \\ \end{pmatrix},\]Let the two inputs to the attention layer be \(E_1 = (x_1, y_1)^T\) and \(E_2 = (x_2, y_2)^T\). The attention logit between them is

\[E_2 W_K^T W_Q E_1 = (a x_1 - b y_1,\,-b x_1 - a y_1) \cdot (-a x_2 + b y_2,\, b x_2 + a y_2) = -(a^2 + b^2)(x_1 x_2 + y_1 y_2).\]Since both \(E_1\) and \(E_2\) lie on a circle, the term \(x_1 x_2 + y_1 y_2\) is simply their inner product. The self-attention logit is

\[E_2 W_K^T W_Q E_2 = -(a^2 + b^2)(x_2^2 + y_2^2) < E_2 W_K^T W_Q E_1.\]This means that the model attends more strongly to the previous token than to the current token. Importantly, however, this effect is achieved not by increasing attention to the previous token, but by suppressing attention to the current token. This distinction is subtle for context length = 2, but becomes crucial for longer contexts.

Longer context length

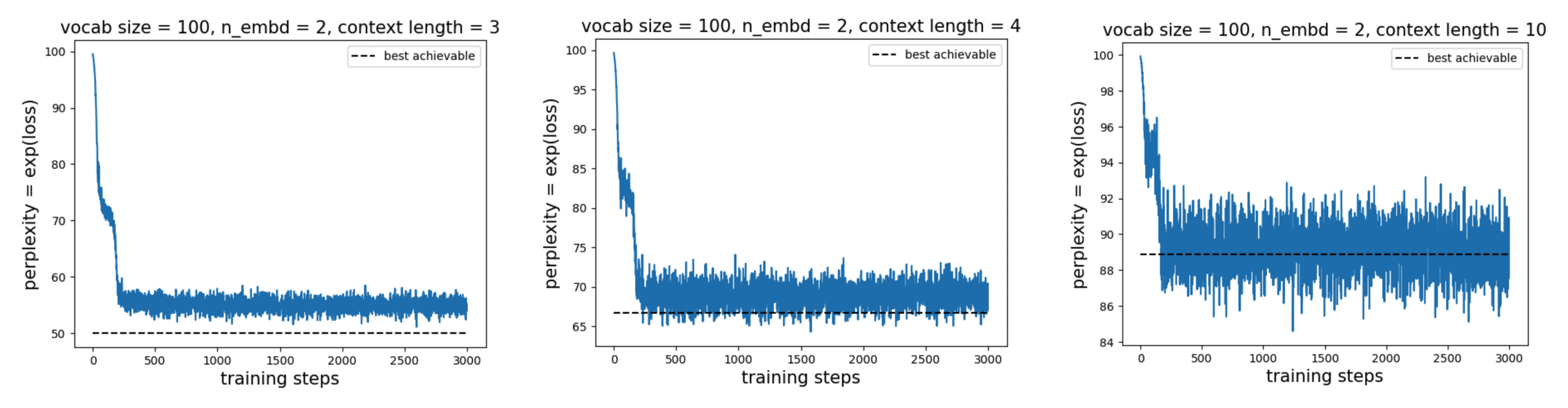

The attention layer has discovered a way to unattend the current token, but it still cannot distinguish among earlier tokens due to permutation equivariance in the absence of positional embeddings. As a result, the model can do no better than guessing: for context length \(C\), it effectively selects one token uniformly at random from the first \(C-1\) tokens, with probability \(\frac{1}{C-1}\) of choosing any particular one. The probability of guessing the wrong token is therefore \(\frac{C-2}{C-1}\).

With vocabulary size \(V\), the best achievable perplexity is thus \(\frac{C-2}{C-1} V\), which is better than pure random guessing \(V\). We verify empirically below:

This suggests that for long sequences, an attention layer without positional embeddings cannot reliably select a specific previous token. Positional embeddings are therefore necessary to implement, for example, a previous-token head. That said, the discovered strategy of unattending the current token is itself an interesting and nontrivial phenomenon.

Acknowledgement

Kaiyue Wen suggests that the sticky plateau might be due to the fact that Sub-n-grams are near-stationary Points (paper).

Code

Google Colab notebook available here.

Citation

If you find this article useful, please cite it as:

BibTeX:

@article{liu2026sparse-attention-1,

title={Sparse attention 2 -- Unattention head, branching dynamics},

author={Liu, Ziming},

year={2026},

month={January},

url={https://KindXiaoming.github.io/blog/2026/sparse-attention-2/}

}

Enjoy Reading This Article?

Here are some more articles you might like to read next: