Physics of AI – How to Begin

In a recent blog post, we mentioned that Physics of AI requires a shift in mindset.

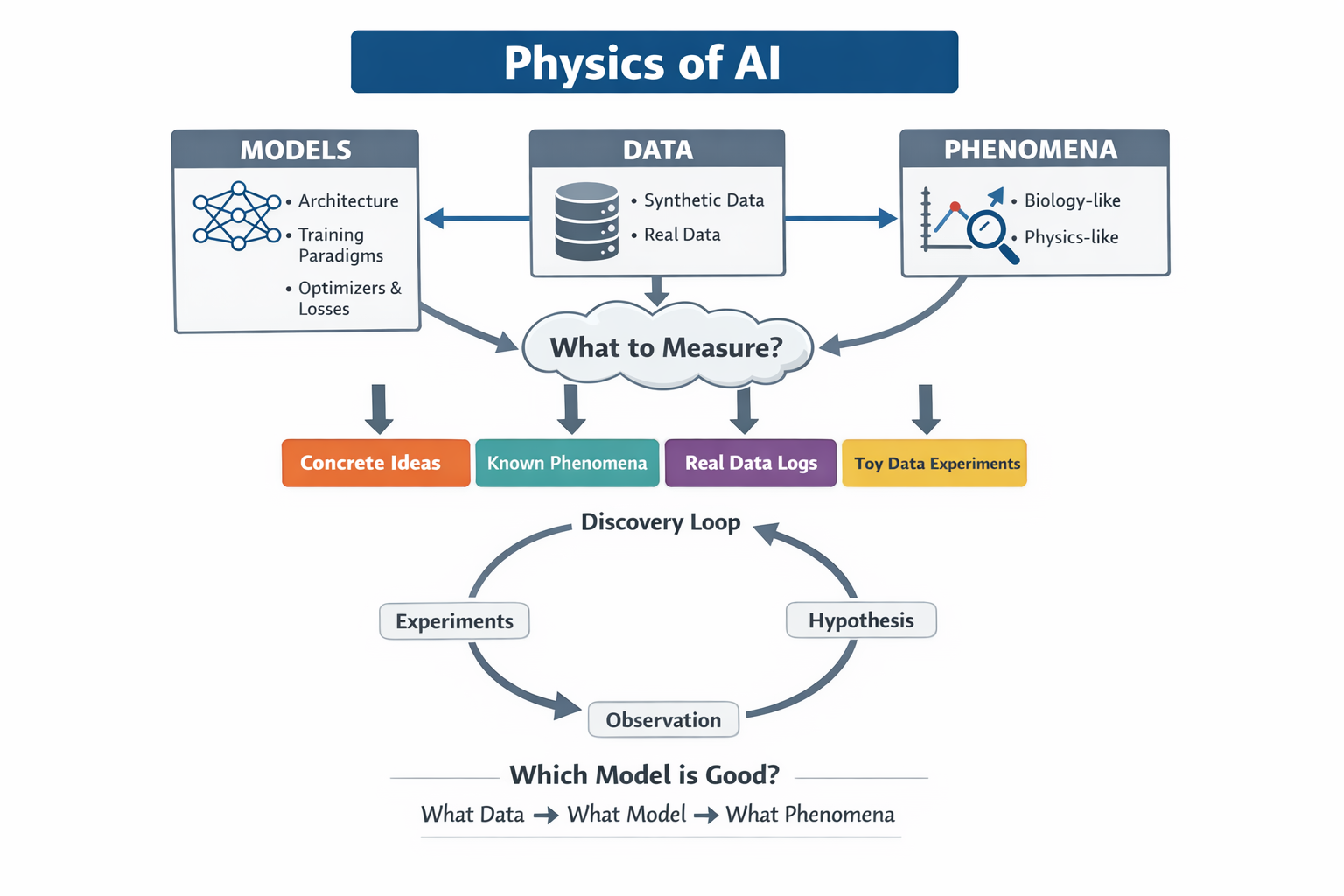

This post will explain, from a slightly more technical perspective, how to do Physics of AI—I will present a modular framework.

On the one hand, we need a framework. With a basic framework, the community can share a common language for communication. On the other hand, we must not be constrained by the framework itself. Physics of AI genuinely requires novel, out-of-the-box ideas.

What Is Physics of AI?

Physics of AI, as the name suggests, means studying AI in the same way we study physics.

It aims to answer the following questions (so simple that they may sound trivial):

What models, on what data, exhibit what phenomena?

(Bonus: why?)

There are three core elements here: models, data, and phenomena.

To emphasize data and phenomena (which are often overlooked by the community), I deliberately fold many details—such as optimizers and loss functions—into the notion of the model.

Below, I elaborate on these three elements.

Models

-

Architecture

Examples include MLPs, RNNs, Transformers, DINO, Mamba, KANs, etc.

Architectures consist of various layers such as MLP layers, attention layers, convolutions, etc. -

Training

- Paradigms

Supervised learning, unsupervised learning, self-supervised learning, representation learning, etc. In the LLM era, we further distinguish pre-training, mid-training, and post-training. - Optimizers

SGD, Adam, Muon, etc. - Loss functions / Rewards

MSE, cross-entropy, accuracy, diffusion loss, etc.

These are often coupled with the training paradigm—for example, contrastive loss in representation learning. - Regularization

L2 weight decay, dropout, KL divergence, and so on.

- Paradigms

Data

- Synthetic (toy) data

We know the data generation process, and have full control over it. - Real data

We do not fully know the data generation process.

Phenomena / Observables

Beyond commonly tracked quantities such as loss curves and accuracy, we also care about:

-

Biology-like phenomena (often data-dependent)

For example, understanding whether (and how) representations, computations, algorithms, or structures emerge during training.

A well-known example is the induction head.

The field of mechanistic interpretability is closely related here. -

Physics-like phenomena (often data-independent)

For example, weight matrix spectra, activation subspaces, attention patterns, and so on.

What Should We Measure?

A central and difficult question in AI phenomenology is: what exactly should we measure?

Of course, this depends on the phenomena we want to observe. But in order to observe phenomena, we must first know which quantities to measure—that is, which observables correspond to which phenomena. This creates a classic chicken-and-egg problem.

We must start somewhere. Based on my experience, common starting points include:

-

Making abstract ideas concrete, which leads to observables.

For example, I may care about feature learning, but features are high-dimensional. I therefore define observables that capture certain aspects of feature learning. In this blog, I use the number of non-linear neurons as one such observable. -

Starting from a known phenomenon and discovering new ones.

For instance, some people study grokking and, during reproduction, discover new phenomena such as loss spikes, which then become a subject of study themselves. This leads to Apple’s slingshot paper. -

Starting from real data, and logging common observables during training.

What counts as “common” requires accumulation of experience:

(i) seeing what others in the field measure, and

(ii) learning which observables were useful in your own past experiments. -

Starting from toy data, imagining how the model should behave (prompting yourself: “If you were an AI model, what would you do?”), and then designing observables to test whether the model actually behaves that way.

In this way, the original chicken-and-egg problem becomes a spiral of ascent:

more phenomena inspire new observables, and new observables lead to the discovery of more phenomena.

Why Does This Phenomenon Occur?

My personal thinking habit is to first ask:

Is this phenomenon caused by the data, or by the model?

Here, “model” also includes random seeds: how sensitive is the phenomenon to the random seed?

The fastest way to get answers is through experiments—changing seeds, changing models, changing data, and checking whether the phenomenon persists. Once these basic experimental results are in hand, we can begin to form hypotheses. Hypotheses predict new observables and phenomena, which are then tested by further experiments.

This forms a discovery loop:

Run experiments → observe phenomena → form hypotheses → design the next experiments

What Does It Mean to “Understand” Something?

There are many layers to asking “why” or claiming understanding. How much understanding is enough?

My personal criterion is: when my predictions are broadly consistent with new experimental results, I consider that a success.

The meaning of “broadly” is subtle. When I am lazy or tolerant, matching trends may be enough. When I am diligent or obsessive, I may want quantitative agreement as well.

For example, the discovery of the \(t\sim \gamma^{-1}\) (\(t\): grokking time, \(\gamma\):weight decay) in our Omnigrok paper came from pushing this obsession further. How far one pushes before stopping largely depends on the researcher’s personality, beliefs, and scientific taste. If we post our findings publicly, the whole community can push the frontier together (we’re all “blind men touching elephants”; different perspectives are always helpful).

What Makes a Model “Good”?

A common debate in the field is: Which model is better?

Is this judgment objective or subjective?

The No Free Lunch theorem already gives the answer: no model is universally better than another across all data.

The real philosophical question is therefore:

What kind of data is the world closest to?

Physics of AI can objectively answer:

what data, under what models, exhibits what phenomena—this part is fully objective and uncontested.

Once we have a notion of which phenomena are desirable (possibly subjective, possibly objective), we can answer:

what data requires what models.

Going one step further, once we have a notion of what kind of data the world is closest to (again, possibly subjective or objective), we can answer:

which models are good.

The current state of AI development often skips the purely objective stage and jumps directly to subjective claims. As a result, discussions often devolve into “you say yours, I say mine,” lacking the shared knowledge required for meaningful communication.

The goal of Physics of AI is precisely to construct this shared knowledge.

Citation

If you find this article useful, please cite it as:

BibTeX:

@article{liu2025physics-of-ai-recipe,

title={Physics of AI – How to Begin},

author={Liu, Ziming},

year={2026},

month={January},

url={https://KindXiaoming.github.io/blog/2026/physics-of-ai-recipe/}

}

Enjoy Reading This Article?

Here are some more articles you might like to read next: