Physics 1 -- Attention can't exactly simulate uniform linear motion

Author: Ziming Liu (刘子鸣)

Motivation

In a recent paper, “What Has a Foundation Model Found? Using Inductive Bias to Probe for World Models”, the authors show that transformers fail to learn planetary motion governed by Newton’s second law under Newtonian gravity. However, the underlying failure modes are not well understood.

As a physicist, I would like to further simplify the setup while preserving the failure mode. In this blog post, we study whether an attention layer can learn Newton’s first law—uniform linear motion. Given the current state \(x_t\) and the previous state \(x_{t-1}\), the next state is \(x_{t+1} = 2x_t - x_{t-1}.\) While this relation is trivial for an MLP mapping \((x_{t-1}, x_t) \mapsto x_{t+1}\) (since it is linear), it is not immediately clear whether an attention layer can learn it efficiently or exactly, because:

- linear coefficients must be constructed through softmax attention;

- softmax attention produces positive weights, whereas the coefficients 2 and −1 have opposite signs.

These concerns may not be fatal, but they are suspicious enough to warrant a closer look through toy experiments.

Problem setup

As Einstein put it, we want a model that is as simple as possible, but not simpler. In this spirit, I start from the simplest possible models, gradually add complexity (sometimes removing it again), and eventually arrive at an architecture that can perform the task reasonably well. I then inspect the weights and representations to understand what kind of algorithm has emerged.

The exploration process is summarized below. Readers who are only interested in the final result can safely skip this part.

- I start with

input_dim = 3(since Euclidean space is 3D), using a 1-layer, attention-only model with a single head and no positional embeddings. It does not learn. - To break the symmetry between positions (coefficients 2 and −1), I add absolute positional embeddings (APE). It still does not learn.

- I then suspect the model is too narrow, since I tied the embedding dimension to the input dimension (3). I decouple them by adding a projection-up layer from 3D to 20D and a projection-down layer from 20D back to 3D. Now it finally learns.

- The model now feels overly complex, so I begin simplifying. I reduce

input_dimfrom 3 to 1. It still learns (not surprising, since the task is easier). - I reduce the embedding dimension to 4. It still learns.

- I reduce the embedding dimension to 2. It fails for one random seed, but succeeds for another.

- I reduce the embedding dimension to 1. With a lucky random seed (after trying a few), it can learn.

- With both

input_dim = 1andembedding_dim = 1, the projection-up and projection-down layers seem unnecessary. However, after removing both, the model fails for all 10 random seeds I tried. If I remove only the projection-down layer but keep projection-up, it can still learn. - I notice that when projection-up is learned, its weight is small (around 0.08). This suggests that to remove it entirely, I should manually rescale the input by a factor of 0.1. With this change, the network learns again.

- Finally, I try removing the bias terms in the attention layer. The network no longer learns. At this point, I stop—the model is already simple enough.

We thus arrive at a model that is as simple as possible while still being able to perform the task \(x_{t+1} = 2x_t - x_{t-1}\) reasonably well. Note that cherry-picking random seeds is not an issue here: the goal is not to demonstrate superior performance (where cherry-picking would be inappropriate), but to gain insight into how simple networks represent and compute.

A simple model can numerically approximate the mapping

In summary, we now have a “transformer” model with:

- 1D input (and 1D embedding),

- context length 2 (using \(x_0\) and \(x_1\) to predict \(x_2\)),

- absolute positional embeddings,

- a single-head, 1D attention layer,

- no MLPs.

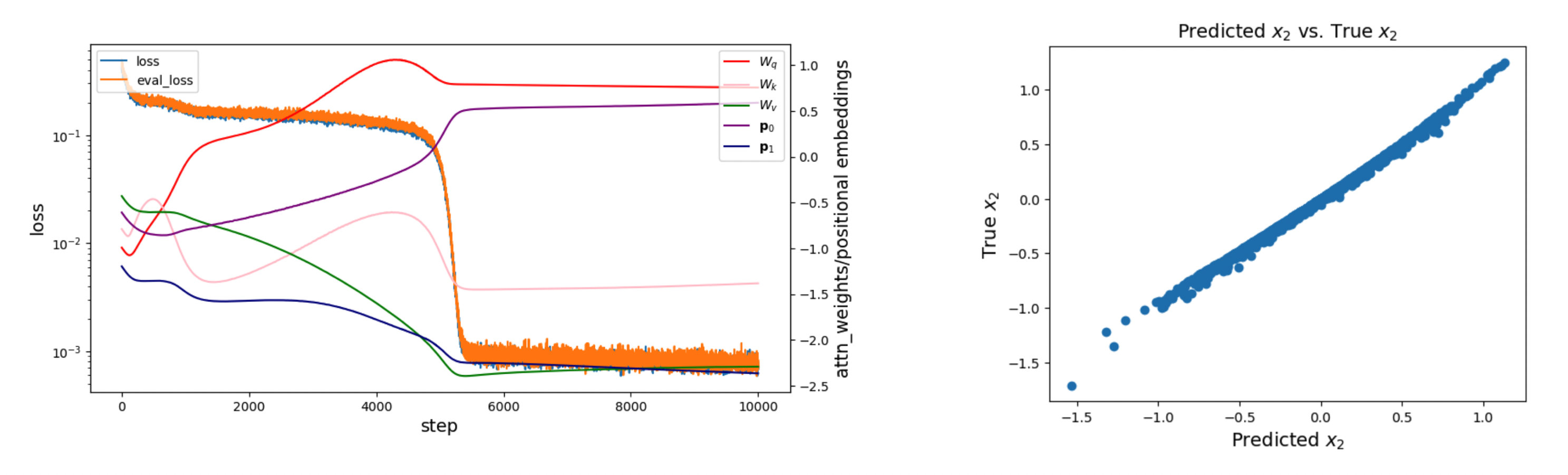

This model can predict \(x_2\) from \(x_1\) and \(x_0\) reasonably well, achieving an MSE loss of about \(10^{-3}\).

The sticky plateau of the loss curve at the beginning of training seems to correspond with the learning of positional embeddings (\(p_0\) and \(p_1\) repulse).

The model does not exactly represent the mapping

We now want to better understand how the model implements the task. A first hypothesis is the following: when positional embeddings dominate the input (i.e., \(x_0, x_1 \ll p_0, p_1\)), the attention matrix becomes approximately constant—roughly independent of \(x_0\) and \(x_1\). In that case, the network would represent \(f(x) = W_v(\alpha_1 x_1 + \alpha_0 x_0),\) where \(\alpha_1 + \alpha_0 = 1\) and \(\alpha_1, \alpha_0 > 0\) (positivity guaranteed by softmax). However, \(2x_1 - x_0\) does not belong to this family, since the two terms have opposite signs. Therefore, the network must be doing something more subtle—in particular, the attention weights must depend on \(x_0\) and \(x_1\).

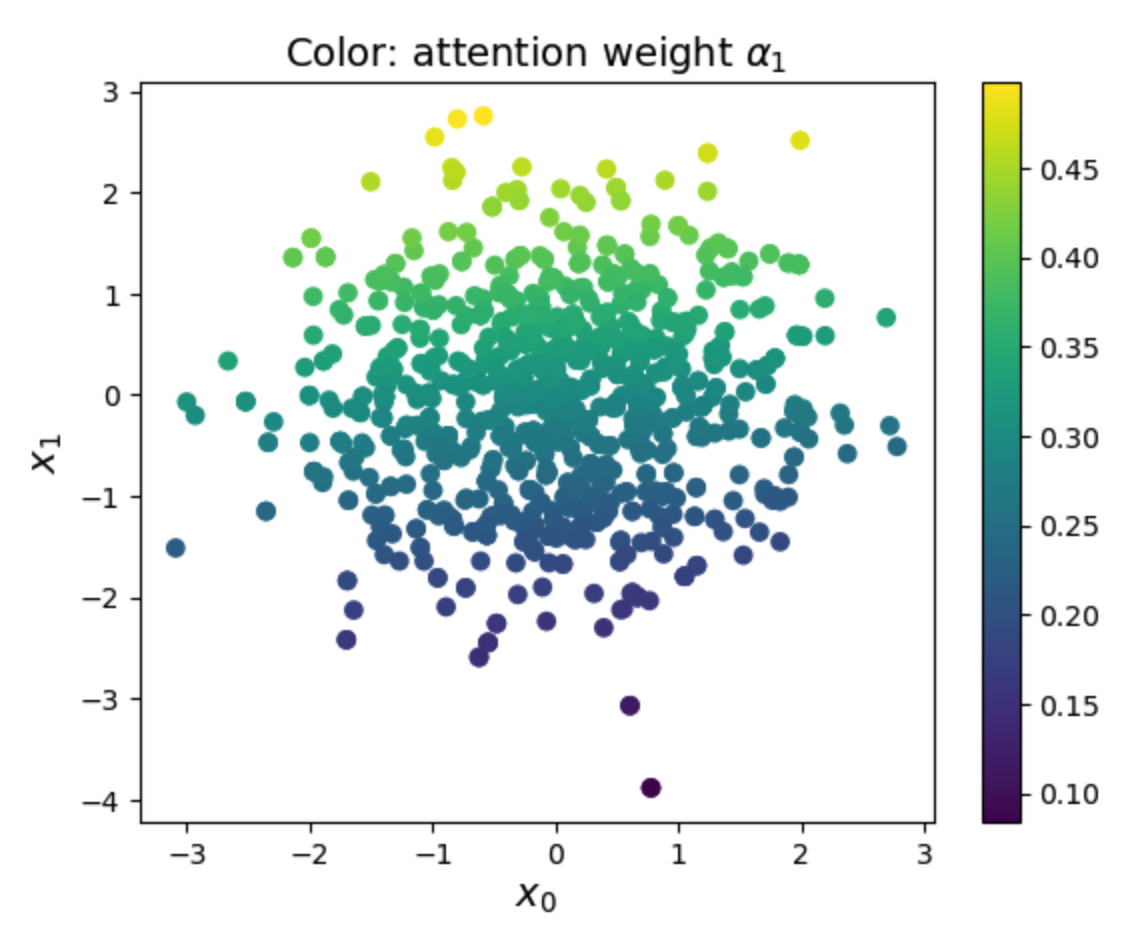

To investigate this, we visualize how \(\alpha_1\) depends on \(x_0\) and \(x_1\). Empirically, \(\alpha_1\) depends primarily on \(x_1\), and the relationship appears roughly linear.

A linear regression gives \(\alpha_1 \approx -0.006 x_0 + 0.068 x_1 + 0.300 \quad (R^2 = 0.996).\) This indicates that although softmax is nonlinear, it is being used only locally, so its dependence is well approximated by a first-order Taylor expansion.

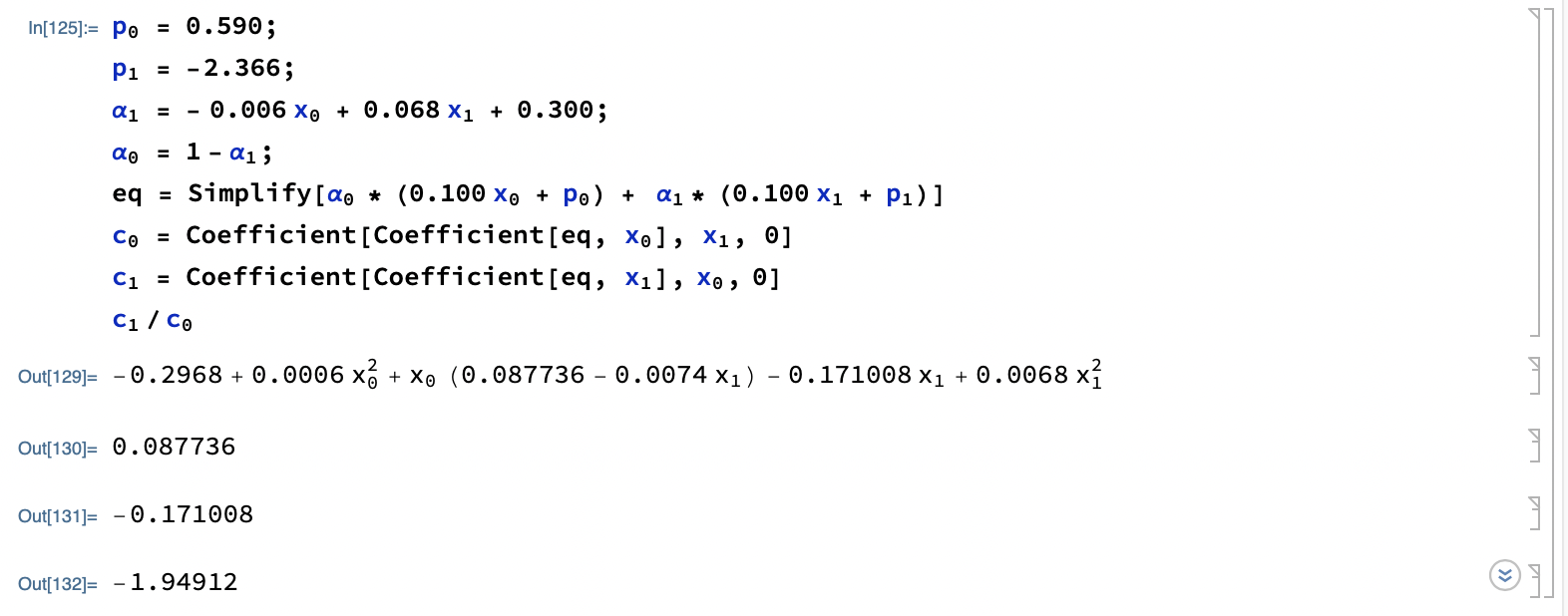

Since attention is the only nonlinear component of the model—and we can approximate it linearly—we can now write down the full computation graph explicitly. We use Mathematica for symbolic computation:

Ignoring quadratic terms, we obtain \(-0.088 x_0 + 0.171 x_1 \approx 0.088(-x_0 + 2x_1).\)

Comment

- Although a 1-layer attention model can approximate \(x_{t+1} = 2x_t - x_{t-1}\), it does so only approximately—by leveraging a local Taylor expansion of the softmax—rather than computing the relation exactly.

- The linear mapping \(x_{t+1} = 2x_t - x_{t-1}\) has a clear physical interpretation as uniform linear motion. This blog shows that even such simple motion cannot be represented exactly by a 1-layer transformer. While adding depth and MLPs may improve the approximation (e.g., by effectively expanding around more nonlinearities to better cancel higher-order terms), I suspect the computation remains approximate rather than exact. This suggests that in order to build real “world models” or “AI Physicists”, we are gonna need model beyond transformers.

Code

Google Colab notebook available here.

Citation

If you find this article useful, please cite it as:

BibTeX:

@article{liu2026physics-1,

title={Physics 1 -- Attention can't exactly simulate uniform linear motion},

author={Liu, Ziming},

year={2026},

month={February},

url={https://KindXiaoming.github.io/blog/2026/physics-1/}

}

Enjoy Reading This Article?

Here are some more articles you might like to read next: