Memory 1 -- How much do linear layers memorize?

Author: Ziming Liu (刘子鸣)

Motivation

I am deeply inspired by the perspective that a language model (or at least some components of it) may behave like a memorization machine. In particular, John Morris and colleagues at Meta attempted to quantify model capacity using random data in the paper “How much do language models memorize?”. They estimate that GPT-style models have a capacity of roughly 3.6 bits per parameter.

In the spirit of the physics of AI, I want to study neural network memorization in a highly simplified setting and aim to understand the behavior as completely as possible. A natural starting point is the simplest nontrivial model: a linear layer.

Problem setup

We consider a linear layer that maps an input \(x \in \mathbb{R}^n\) to logits \(\ell \in \mathbb{R}^V\). We construct a random-label dataset with \(N\) samples: each input \(x\) is drawn from a standard Gaussian distribution, and each label is a randomly chosen one-hot vector.

If the network predicts a sample’s label correctly, we say that the sample is memorized. Let \(C(N)\) denote the number of memorized samples. We train the linear layer using the cross-entropy loss and the Adam optimizer.

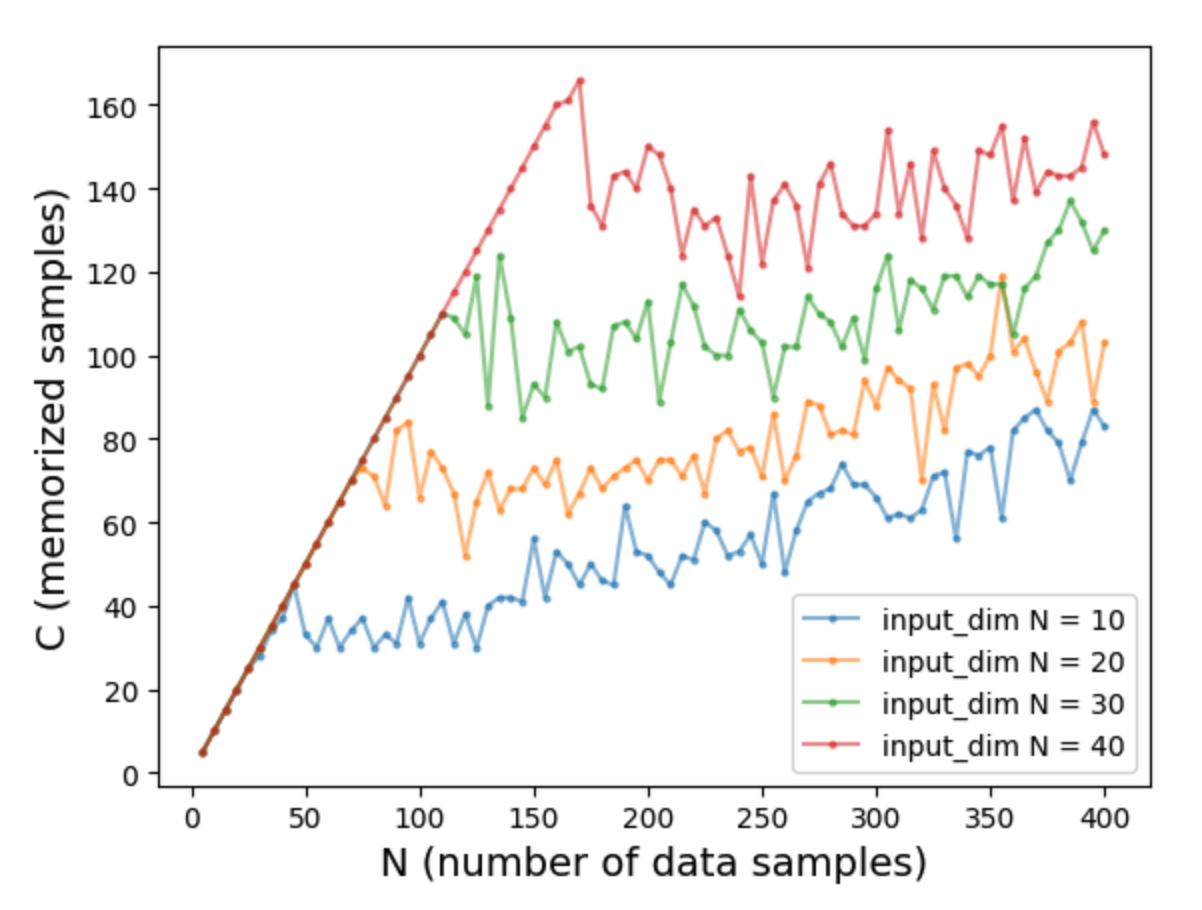

Finding 1: \(C(N)\) for different \(n\)

We fix \(V = 40\) and sweep the input dimension \(n = 10, 20, 30, 40\), as well as the dataset size \(N = 5, 10, \ldots, 400\).

We observe that for each \(n\), \(C(N)\) initially grows linearly—corresponding to memorizing all samples—and then saturates. This behavior is also reported in “How much do language models memorize?”. However, there are two subtle differences:

- For input_dim = 10, the “saturation” regime still exhibits a positive slope.

- For input_dim = 40, performance in the saturation regime is worse than at the peak of the linear-growth regime.

We find that both effects depend on the learning rate. Since we use a fixed learning rate of 0.01 across all input dimensions, this value is too small for input_dim = 10 and too large for input_dim = 40.

Additionally, the effective capacity appears to scale linearly with \(n\): for \(n = 10, 20, 30, 40\), the capacity is roughly \(40, 80, 120, 160\), respectively.

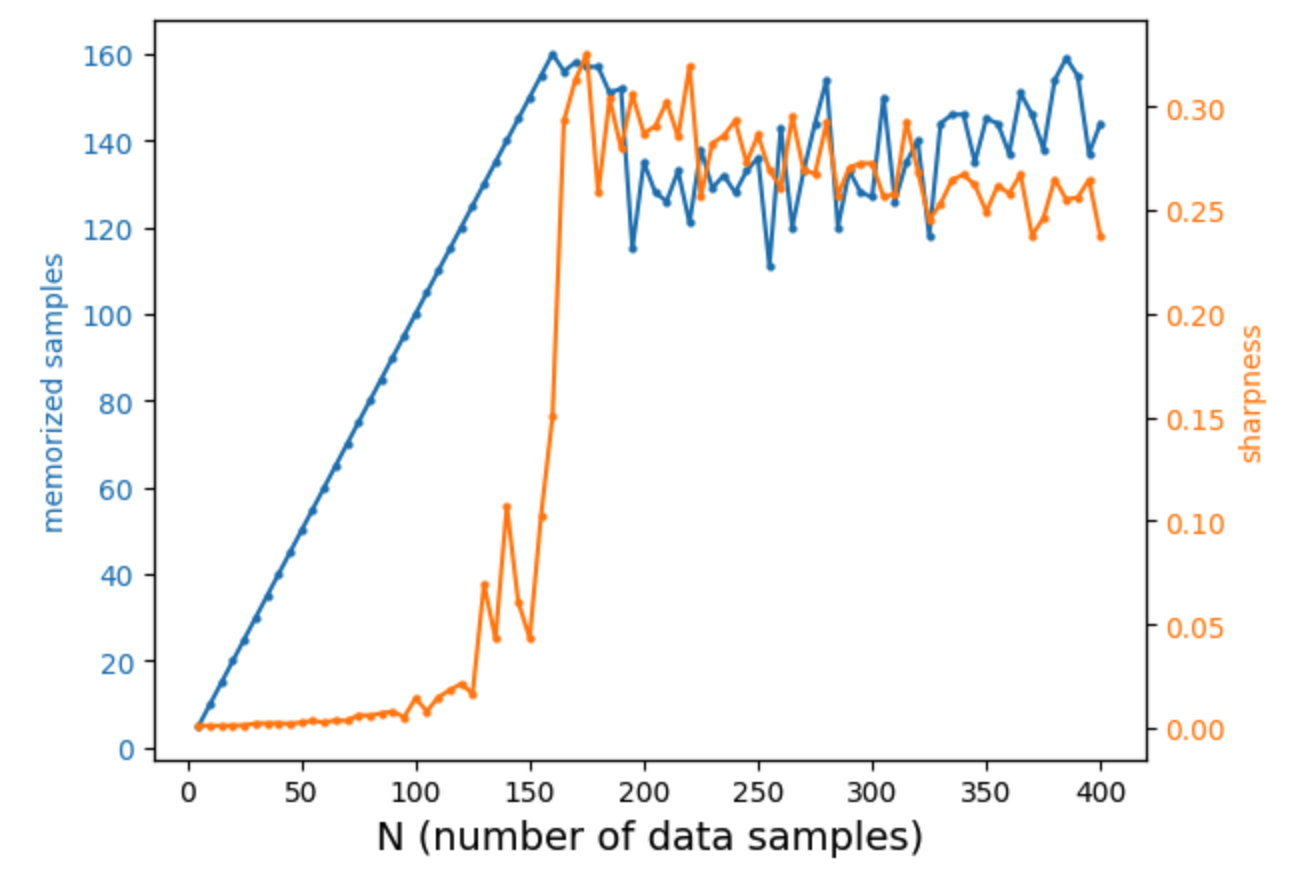

Finding 2: Memorization, sharpness, and jamming

For input_dim = 40, we find that the saturation phase performs slightly worse than the best point in the linear-growth phase. We conjecture that this is due to gradient conflicts when the number of samples becomes large. Such conflicts can create narrow “valley directions” in the loss landscape (see, for example, “Understanding Warmup-Stable-Decay Learning Rates: A River Valley Loss Landscape Perspective”), where smaller learning rates are needed.

This intuition is closely related to the jamming phase transition: placing a single ball into an empty box is easy, but adding a new ball into an already crowded box requires much more care—analogous to using a smaller learning rate.

We define sharpness as the largest eigenvalue of the Hessian of the loss function. Indeed, as the number of data points increases, we observe a sharp phase transition near the memorization capacity. Beyond this point, the loss landscape becomes significantly sharper, requiring smaller learning rates for stable optimization.

Finding 3: Which samples are memorized?

A natural hypothesis is that samples with low loss at initialization are more likely to be memorized. However, this does not appear to be the case: we find no clear correlation between a sample’s initial loss and its final loss.

Instead, the model appears to exploit statistical biases in the finite dataset. Although the underlying data distribution is random and symmetric in expectation, a finite sample can exhibit incidental biases that the network can learn and exploit. Samples that align with these emergent patterns are more likely to be predicted correctly.

As a simple analogy, consider flipping a fair coin 100 times and obtaining 52 heads and 48 tails. To minimize loss (or maximize accuracy), a model would predict “heads,” even if it were initially biased toward predicting “tails.”

Code

Google Colab notebook available here.

Citation

If you find this article useful, please cite it as:

BibTeX:

@article{liu2026memory-1,

title={Memory 1 -- How much do linear layers memorize?},

author={Liu, Ziming},

year={2026},

month={February},

url={https://KindXiaoming.github.io/blog/2026/memory-1/}

}

Enjoy Reading This Article?

Here are some more articles you might like to read next: