Fine-tuning with sparse updates? A toy teacher-student Setup

Author: Ziming Liu (刘子鸣)

Motivation

When we fine-tune a model, do we really need to update all layers?

For language models, my mental picture is that the model can be divided along depth into three parts:

- early layers: mapping tokens → latent space

- middle layers: performing reasoning in latent space

- late layers: mapping latent space → tokens

As long as a task is still expressed in natural language, the mapping between language space and latent space should be largely fixed. Therefore, during fine-tuning, perhaps it is sufficient to fine-tune only the middle layers. How can we test this hypothesis?

There are three possible approaches:

-

Method 1: Fine-tune only the middle layers and check whether it works.

However, to judge effectiveness, we need baselines (e.g., only fine-tuning early layers, or only fine-tuning late layers). The number of baselines grows exponentially, since each layer can either be frozen or fine-tuned. -

Method 2: Train normally and examine how the magnitude of parameter updates varies across layers.

The problem is that update magnitudes are highly influenced by the optimizer. For example, even if some layers have very small gradients (and arguably do not need to change), adaptive optimizers may still update them. -

Method 3: Train normally, but impose sparsity on the updates (by adding L1 regularization), and then examine how update magnitudes vary across layers.

This approach may avoid the issue in Method 2.

In this article, we use a teacher–student model to explore Methods 2 and 3. We find that Method 2 indeed suffers from the suspected issue, while Method 3 can effectively resolve it.

Teacher–student setup

We adopt a teacher–student setup: the Teacher Network and the Student Network are MLPs with identical architectures.

The teacher network is randomly initialized and generates input–output pairs. The student network is trained in a supervised manner to minimize the MSE loss of output predictions.

Some layers of the student network are copied from the teacher network, while the remaining layers are randomly initialized. Motivated by the discussion above, we consider a three-layer MLP. At initialization:

- the first and third layers of the student network are identical to those of the teacher network,

- the second layer is randomly initialized (and thus different from the teacher network).

During training, we additionally compute the L1 distance between the student network at training time and its initialization, and use this as a regularization term to encourage sparse updates. The strength of this regularization is denoted by \(\lambda\).

The student network can be interpreted as a pretrained model, while the teacher network serves as a fine-tuned data generator. We ask whether the student network can “realize” that it actually does not need to update the first and third layers.

We define two sets of observables to characterize the training dynamics:

- the distance between the student network during training and its initialization,

- the distance between the student network during training and the teacher network.

Specifically, we compute the L1 distances for \(W_1, W_2, W_3, b_1, b_2, b_3\).

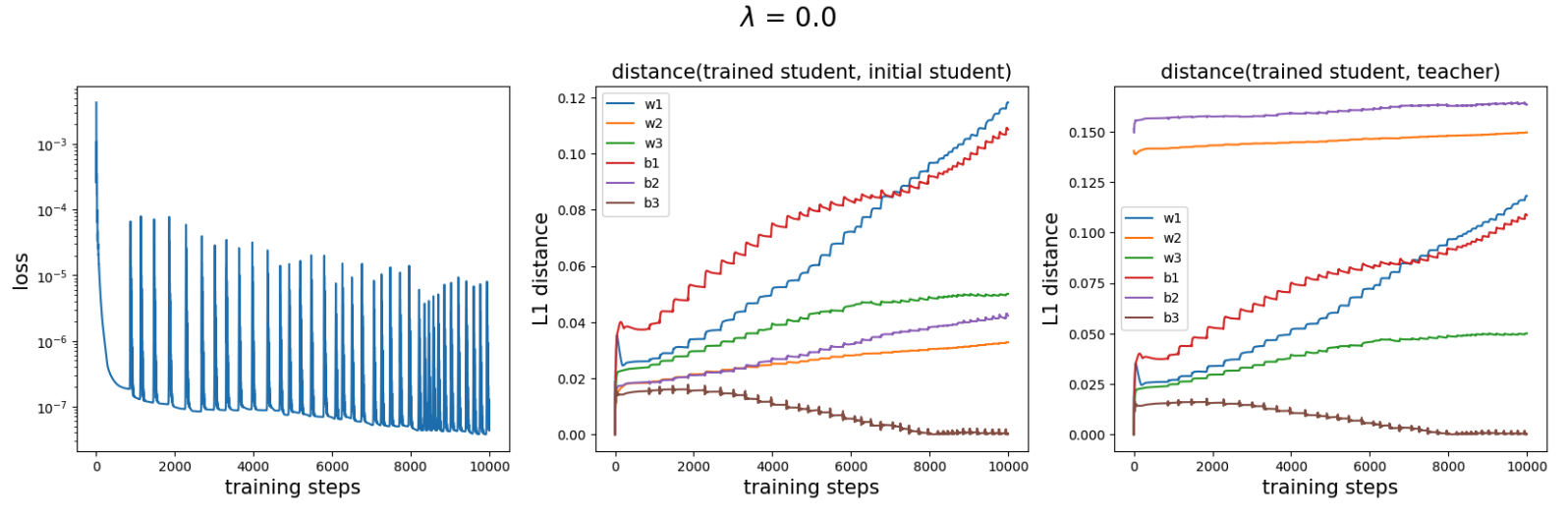

Normal training (\(\lambda = 0\))

We find that the update magnitude of \(W_2\) is actually smaller than that of \(W_1\) and \(W_3\). This shows that Method 2 is unreliable.

Additional observation. Each spike in the loss curve corresponds to a “step” in the weights. This phenomenon may be related to the slingshot mechanism.

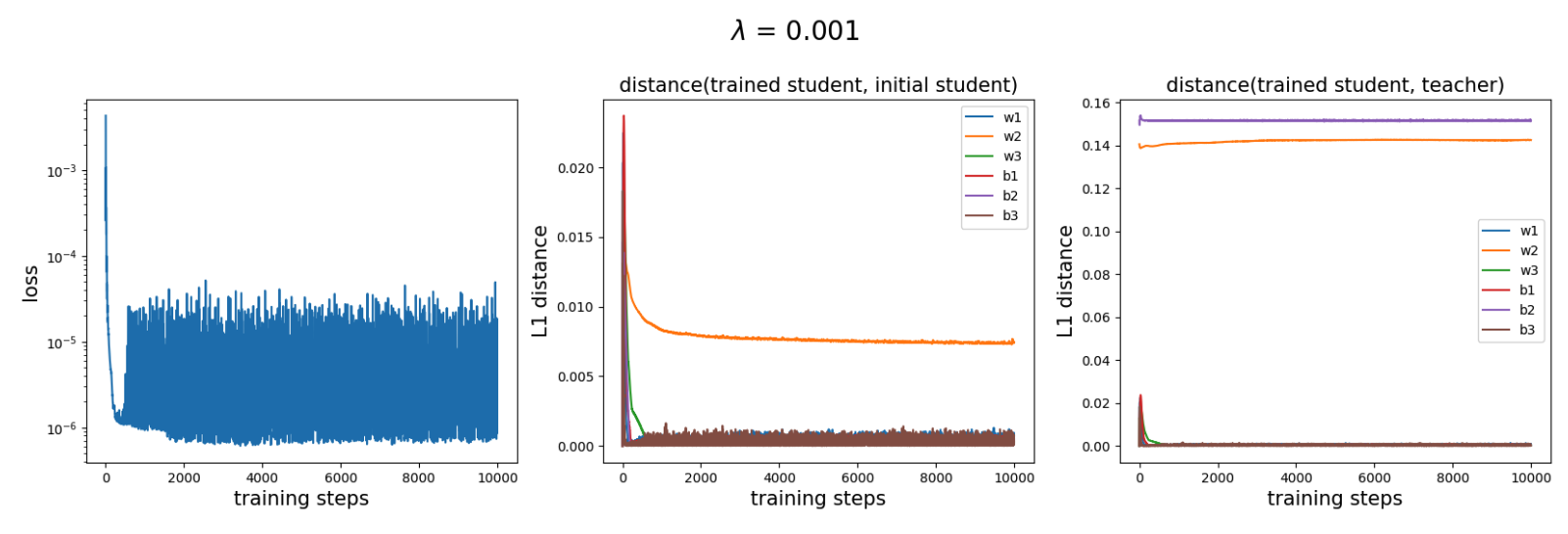

Sparse updates (\(\lambda = 0.001\))

We find that only \(W_2\) has a significantly non-zero update, while the updates of all other weights eventually approach zero (although they may move substantially at the beginning, which is likely an artifact of Adam). This indicates that sparse updates can reveal the intrinsic structure of the data—namely, that only the middle layer needs to be fine-tuned.

Additional observation. The distance between the trained student network and the teacher network for \(W_2\) does not converge to zero (and is in fact quite large). This may be because \(W_2\), acting on sparse inputs, is effectively low-rank, so the optimal \(W_2\) is not unique.

Questions / Ideas

-

Fine-tuning with sparse updates can serve as an interpretability tool—revealing layer-wise similarity between two datasets.

Given a model pretrained on dataset A and fine-tuned on dataset B with sparse updates, it would be interesting to see which layers undergo large updates and which remain nearly unchanged. -

L1 regularization could be replaced by other metrics (e.g., the nuclear norm to encourage low-rank structure, to accompany LORA).

-

Can this method be scaled up, and if so, how?

-

Could this approach help with continual learning?

Sparse updates may mitigate catastrophic forgetting.

Code

Google Colab notebook available here.

Citation

If you find this article useful, please cite it as:

BibTeX:

@article{liu2026fine-tuning-sparsity,

title={Fine-tuning with sparse updates? A toy teacher-student Setup},

author={Liu, Ziming},

year={2026},

month={January},

url={https://KindXiaoming.github.io/blog/2026/fine-tuning-sparsity/}

}

Enjoy Reading This Article?

Here are some more articles you might like to read next: