What's the difference -- (physics of) AI, physics, math and interpretability

In a previous blog post, I discussed how to conduct Physics of AI research. Some friends later asked: Can AI and physics really be fully analogous? And what is the difference between Physics of AI and interpretability?

This article will discuss two points:

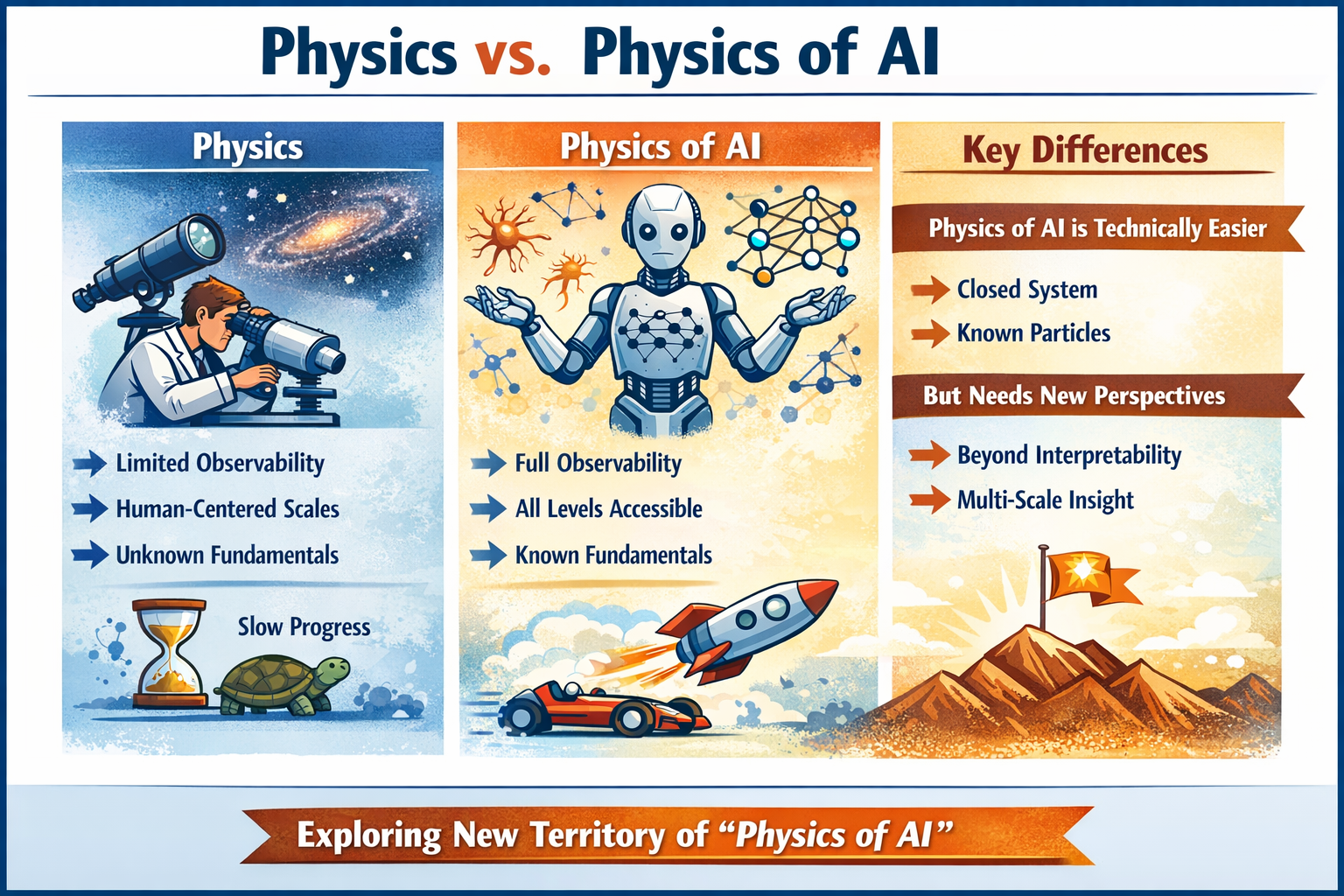

- AI and physics are not fully analogous, but that does not prevent us from borrowing methodologies from physics. In fact, Physics of AI is technically a simpler game than physics. Its main obstacles lie in publication culture (as discussed in a previous blog post), not in the intrinsic difficulty of the subject.

- (As I define) Physics of AI is not the same as (what people usually define) interpretability. The key reason is that I see some genuinely new research perspectives that deserve a new name. What that name is does not really matter. If, in the future, the community expands the definition of interpretability, I would also be happy to simply call it interpretability.

First, what’s the difference between physics and (physics of) AI?

Physics

If we count from the time of Newton, physics has taken about 400 years to develop to its current state. Compared with the development of AI, this is extremely slow. This slowness comes from both practical constraints and philosophical constraints.

Practical constraints — physics research has strong directionality

- Experiment-driven: theories emerge from experimental observations.

- “Human-centered” scales: starting from scales directly accessible to human perception, then extending in both directions—toward the microscopic (atoms, quarks) and the macroscopic (celestial bodies, the universe).

Both directions are constrained by experimental and observational bottlenecks. It takes a long time to build microscopes and telescopes in the physical world.

Philosophical constraints

We do not actually know how the “creator” (physical laws) truly runs the universe. We can only infer laws from phenomena.

All models are wrong, but some are useful.

Even the most committed reductionists are troubled by two questions:

- Minimum and maximum scales: Are fundamental particles truly fundamental, e.g., can quarks or electrons be further divided? What lies beyond the universe?

- Cross-scale emergence: How do phenomena at different levels “emerge” from one another?

(Physics of) AI

For AI, none of the above constraints really exist.

No practical constraints

Apart from computational limits that prevent us from reaching arbitrarily large scales, we have no observational limitations. In principle, we can study the evolution of all weights and all neurons.

No philosophical constraints

We fully understand the “fundamental particles” of AI (neurons, weights, gradient descent), and we know the “boundary of the universe” (the entire neural network). We are the creator.

In principle, we can observe phenomena at any level at any time. There is no inherent directionality and no “human-centered” scale. AI systems are also closed systems—we know exactly how they evolve because we train them ourselves. Therefore, in principle, it must always be possible to explain large-scale phenomena using small-scale mechanisms, even if such explanations are not always useful.

Physics is different: the continual discovery of “new physics” shows that its boundaries are still being broken.

Mathematics

At this point, it is tempting to equate the physics of AI with mathematics, since both have clearly defined “fundamental particles”—called axioms in mathematics. But mathematics is clearly more difficult, for several reasons:

- Mathematics is also largely directional: starting from axioms and deriving results is a process from “microscopic” to “macroscopic.” In contrast, AI phenomenology can be studied simultaneously at multiple levels.

- Symbolic spaces make the definition of scales/levels and observations difficult: although backward reasoning (induction, abduction) exists in mathematics, it is often hard to define what “intermediate reasoning” even means, because symbolic spaces can be infinite. Neural networks (current AI systems), by contrast, have bounded topologies — no smaller than a neuron and no larger than the entire network.

- Cultural emphasis on rigor: mathematical rigor often comes at the cost of faithfulness to reality. AI research, in contrast, emphasizes practicality and is far less obsessed with rigor. Physics lies somewhere in between mathematics and AI in terms of rigor.

Does the Physics of AI Have No Difficulties, Then?

Of course not.

Philosophically, the physics of AI does not suffer from reductionism problems (we know the minimum and maximum scales, and cross-scale explanations are possible in principle). However, it may still face technical challenges. Even so, I remain optimistic. Two major technical questions are:

- How do we define levels and corresponding observations? Neurons, weights, and representations are clear, but how should we define circuits or modules? Once levels are defined, what observables should we introduce, and what phenomena should we observe? I gave partial answers in this blog post.

- How do we characterize the connections (emergence) between levels? In principle, because AI systems are closed, lower-level phenomena should always be able to explain higher-level ones. In practice, however, finding explanations that are simple and useful is still a non-trivial problem. To be honest, I still have no clue how to answer this question. But more hands-on experiments will give the answer.

Response to Critiques from the Scaling Camp

The issue of emergence is the main line of attack from the scaling camp against the research camp:

How can phenomena observed in small models transfer to large models?

Below is my response/attitude/belief:

Philosophical level

- In natural science, analogies of emergence do not straightforwardly apply here (as discussed above). The ineffectiveness of reductionism in explaining emergence in nature (e.g., Hilbert’s sixth problem is a hard problem) does not imply the same ineffectiveness in AI. Moreover, I personally do not like the word “emergence” since it seems to imply something mysterious (which might be appropriate for natural science, but not AI).

- Believe in shared explanations. Phenomenon A in small models and phenomenon B in large models may originate from the same cause. The absence of A in large models does not invalidate the value of studying it.

Methodological level

- Be pragmatic. There are many concrete things we can do that have not yet been done. Only by doing them can we know whether they are useful.

- Be specific. Cross-scale phenomena usually fall into three categories:

- Expansion: phenomenon A in small models becomes more pronounced in large models.

- Shrinkage: phenomenon A in small models becomes less visible in large models.

- Transformation: phenomenon A in small models turns into phenomenon B in large models.

The scaling critique focuses on shrinkage. We are betting on expansion and transformation. Even if everything turns out to be shrinkage, our efforts are still not meaningless—at that point, I would more firmly side with the scaling camp.

- We must acknowledge that academia cannot afford to train the largest models. We should call on large-model companies to open-source models—or at least open-source phenomena. Of course, academia must first identify interesting observables in toy and small models, so that industry knows what to observe.

Interpretability

In a broad sense, interpretability includes everything—one could even say that physics itself is about interpreting the universe. In that sense, the physics of AI certainly belongs to interpretability.

However, what people usually mean by interpretability refers narrowly to interpretability research in AI, and their understanding is constrained by past work:

- Some believe interpretability is just storytelling—pleasant but useless.

- Others believe interpretability is mathematics—rigorous but useless.

- The characterizations are often too coarse, making it unclear whether we are studying causality or correlation. This is precisely what mechanistic interpretability seeks to break away from.

- There is a lack of methodology: at what level does an explanation count as complete?

Physics of AI differs from interpretability in all aspects:

- Starts with phenomenology, emphasizing faithful recording of phenomena and reducing the “storytelling” aspect (see previous blog post).

- Is not mathematics (as discussed above). But we can adopt mathematical tools when they are useful.

- Characterizes phenomena at multiple levels, although I personally perfer startting from smallest “toy” models. You might have noticed that my recent technical blogs all study very simple models. The toy models already demonstrate very rich phenomena and I believe that the phenomena in toy models can transform (although maybe not directly transfer) to phenomena in larger models.

- Gradually builds a methodology to describe the connections between phenomena across levels.

Therefore, we deserve a new name for what we are doing. Physics of AI is the name I chose.

Again, the name itself is not important. What matters is that it signals new territory and new treasures.

Citation

If you find this article useful, please cite it as:

BibTeX:

@article{liu2025physics-of-ai-recipe,

title={What's the difference -- (physics of) AI, physics, math and interpretability},

author={Liu, Ziming},

year={2026},

month={January},

url={https://KindXiaoming.github.io/blog/2026/ai-physics-interpretability/}

}

Enjoy Reading This Article?

Here are some more articles you might like to read next: