Achieving AGI Intelligently – Structure, Not Scale

TL;DR: Structuralism AI is the inevitable path beyond scaling — not because scaling is wrong, but because it will eventually hit the energy/data wall.

Scaling laws have been the most important guiding principle in AI over the past few years. That much is undeniable. They have driven unprecedented performance gains and largely unified both industry and academia around a single direction. Yet the logic behind scaling laws is surprisingly simple: because AI struggles with Out-of-Distribution (OOD) tasks, the most straightforward solution is to collect more data and train larger models, until everything becomes In-distribution.

Scaling laws therefore offer a future that is robust, but inefficient.

Let me be very clear about my position. If we completely ignore constraints on energy and data, I do not doubt that pure scaling alone can eventually reach AGI. I have never doubted this. If compute were infinite and data unlimited, large models could, in principle, cover everything. The problem is precisely that the real world is not like this.

So the question becomes:

is there a more intelligent way to achieve AGI?

I believe there is.

And the answer is not more scale, but more structure.

It is important that I deliberately use the word structure, not symbol. This distinction is intentional, and I will explain it later.

Why do we need structure? Because structure enables compression. And compression lies at the core of intelligence. As Ilya once put it: Compression is intelligence.

Consider a simple example. If fractal structure is allowed, the intrinsic complexity of a snowflake is extremely low—it is highly compressible. If structure is disallowed and one must describe it point by point, the apparent complexity of a snowflake is effectively infinite. Today’s scaling laws resemble the latter approach: using ever more parameters and computation to fit massive apparent complexity.

A deeper example comes from celestial mechanics. The most direct way to model planetary motion is to store the positions of planets at every moment in time—a lookup table with enormous cost. Kepler achieved the first true compression by realizing that planetary orbits are ellipses, a global structure in time that dramatically reduced complexity. Newton achieved the second compression by discovering local dynamical laws that explained even more with fewer parameters.

And where does modern AI stand? Work by Vafa and collaborators shows that Transformers do not naturally learn Newtonian world models. This means that correct physical structure does not reliably emerge from scale alone.

Our current expectation that “structure will eventually emerge” often resembles primitive humans praying to gods. The only difference is that our sacrifices—data and compute—actually work (to some extent). And precisely because they work, we lack sufficient motivation to search for a more scientific, more intelligent path forward.

Structure is explicit and everywhere in the natural sciences. In fact, without structure, there would be no natural science at all.

If we draw an analogy with the Tycho–Kepler–Newton trajectory, today’s AI still largely lives in the Tycho era: experiment-driven, data-driven, with only the beginnings of a Keplerian phase—empirical laws such as scaling laws. But unlike the history of celestial mechanics, we have turned these empirical laws into articles of faith, aggressively scaling experiments and engineering systems around them, rather than treating them as clues toward a deeper theory—a “Newtonian mechanics of AI.”

From an intellectual perspective, this is not progress. It is regression.

At this point, you might say: “This is just another piece criticizing scaling and foundation models.”

It is not.

My stance is clear and neutral. According to the No Free Lunch theorem, every model has its domain of applicability and its limitations. Or, more bluntly: All models are wrong, but some are useful.

The real issue is not whether to use foundation models, but whether we understand that different tasks possess fundamentally different structures and compressibility. From a compression perspective, and by analogy with the natural sciences, tasks fall naturally into categories. Some are “physics-like”: highly compressible, with symbolic formulas emerging from continuous data. Some are “chemistry-like”: substantially compressible, with clear structure but incomplete or approximate symbols. Others are “biology-like”: only weakly compressible, dominated by empirical regularities and statistical induction. Pure noise exists as well, but no model can handle it, so we can safely ignore it.

An ideal intelligent system should be able to recognize which kind of task it is facing and apply the appropriate degree of compression.

Symbolic models excel at physics-like tasks but fail on chemistry- and biology-like ones. Connectionist models, due to their generality, can in principle handle all types—but precisely because they lack structure, they are extremely inefficient on physics- and chemistry-like problems.

| | "Physics-like" tasks | "Chemistry-like" tasks | "Biology-like" tasks |

|---|---|---|---|

| **Symbolism AI** | Excellent | Poor | Poor |

| **Connectionism AI** | Inefficient | Inefficient | Good |

| **Structuralism AI** | Good | Good | Good |

This is why I argue for Structuralism.

Symbolism starts from physics-like tasks. Connectionism starts from biology-like tasks. A natural question follows: can we build AI starting from chemistry-like tasks? Structuralism, by design, aims to capture this intermediate regime. We want symbols—stricter, more discrete structures—to emerge from structure, and we want empirical regularities—looser structures—to be learned by relaxing structure from data.

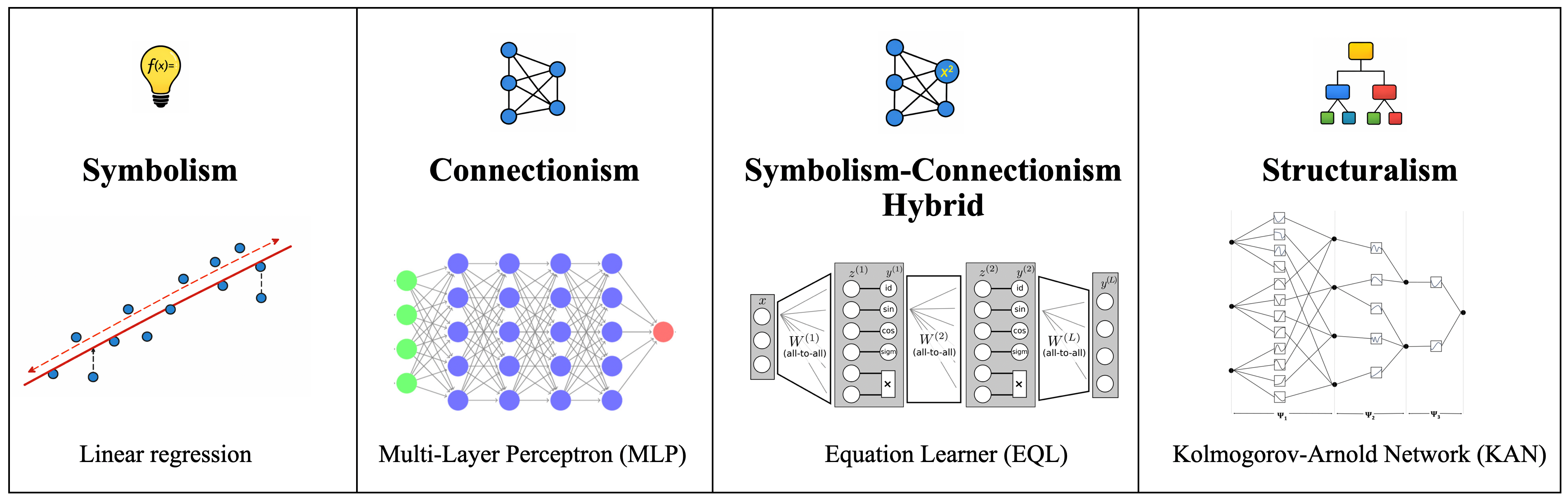

In supervised learning, this distinction is already quite concrete. Linear regression is symbolic. Multi-layer perceptrons are connectionist. EQL represents a neural–symbolic hybrid. Kolmogorov–Arnold Networks (KANs), by contrast, are structuralist. The representation theory underlying KANs compactly captures the compositional structure of multivariate functions. As a result, KANs are neither structureless like MLPs, nor overconstrained like linear models, nor plagued by instability from neural–symbolic mismatch.

Structuralism is not a compromise. It is a unification.

But the real world goes far beyond supervised learning. We do not merely learn structure from data—we compare structures, reuse structures, and build “structures of structures” (category theory!). This is abstraction.

I want to argue explicitly: abstraction is one of the central bottlenecks to AGI. This aligns closely with Rich Sutton’s emphasis on abstraction in OaK architecture. Continual learning is fundamentally about preserving abstract invariances across tasks. Adaptivity and fluidity—for example in ARC-AGI—is about in-context abstraction. And many ARC-AGI tasks are, at their core, simplified forms of intuitive physics, an essential element of world models.

So how do we enable abstraction? I will be honest: I do not yet have a complete solution.

One insight is that abstraction arises from comparing and reusing structures. Attention is also a mechanism for comparison, but it implicitly assumes that structure can be embedded into vector spaces and that similarity can be measured by dot products. In reality, most structures are not isomorphic to vector spaces. We do this largely because it fits GPU computation, not because it is cognitively or scientifically correct.

I believe current AI development is secretly structuralist, but mostly in an extrinsic sense. Reasoning is structured. Agent frameworks are structured. Yet the underlying models remain connectionist. This is extrinsic structuralism, and it relies heavily on Chain-of-Thought-like data to explicitly supervise structure.

I am willing to bet that the next wave of progress will come from intrinsic structuralism: injecting general-purpose structure into models, or enabling structure to emerge internally, without relying on explicit CoT supervision.

From an application perspective, the AGI we actually need must be efficient, adaptive, generalizable, and physically grounded. Structure is essential to all four. The physical world itself is highly structured and highly compressible—compositionality, sparsity, temporal locality. Without these structures appearing in our models, world models will remain out of reach.

In summary, Structuralism AI represents a path fundamentally different from scaling. It may be harder, but it is also more interesting, richer in opportunity, and far more promising in the long run.

In 2026, it’s time to bet/work on something different.

Citation

If you find this article useful, please cite it as:

BibTeX:

@article{liu2025structuralism-ai,

title={Achieving AGI Intelligently -- Structure, Not Scale},

author={Liu, Ziming},

year={2025},

month={December},

url={https://KindXiaoming.github.io/blog/2025/structuralism-ai/}

}

Text citation:

Liu, Ziming (December 2025). Achieving AGI Intelligently – Structure, Not Scale. KindXiaoming.github.io. https://KindXiaoming.github.io/blog/2025/structuralism-ai/

Enjoy Reading This Article?

Here are some more articles you might like to read next: